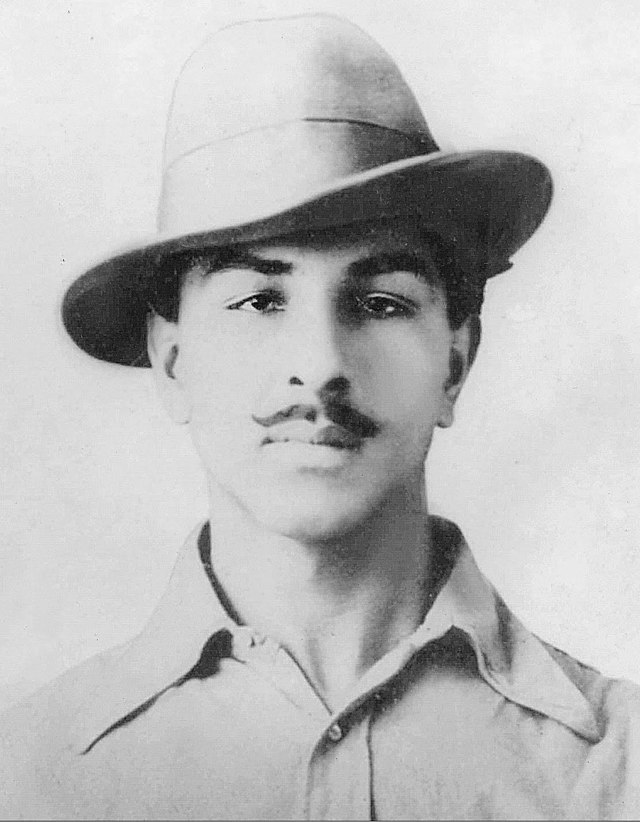

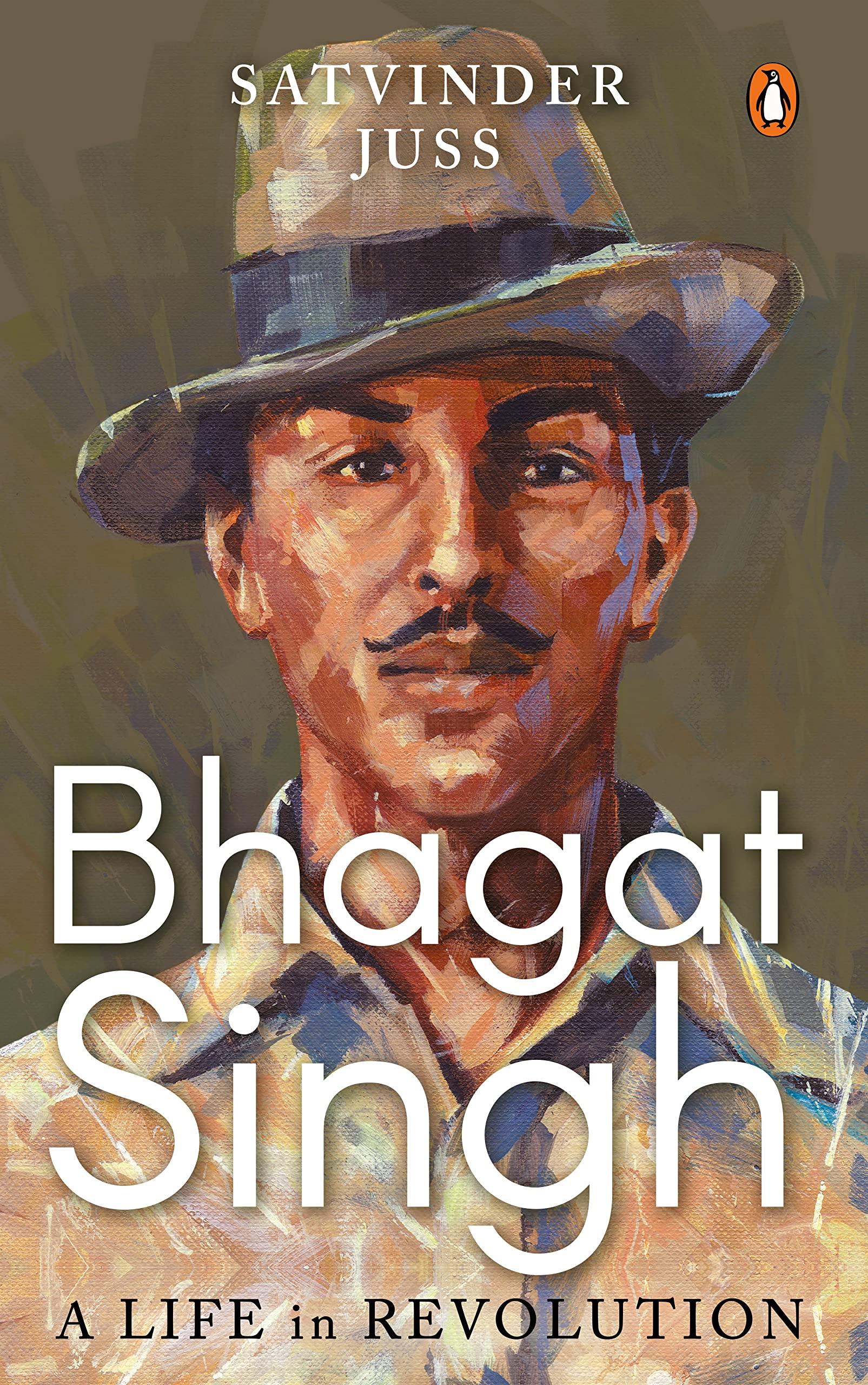

The book “Bhagat Singh: A Life in Revolution” by Satvinder Juss is the definitive Bhagat Singh biography of our times.

The volume deliberates upon his family from before when he was born, examining along the way the role that various episodes, policies and people played in shaping the identity of a legendary revolutionary, while also delving into his opinions on important questions of the time.

The book shines a bright light on the oft-ignored personal influences that made Singh who he was, along with the issue of his contested identity in today’s politics.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

So, how should we interpret Bhagat Singh? While it is absolutely important to take Bhagat Singh’s ideas and writings seriously, there is not much to be gained in calling him the ‘Indian Frantz Fanon’. Bhagat Singh was after all writing so many years earlier in a very different global conjuncture, and there are themes that are so vital to Fanon—race, consciousness, psychology—that do not appear in Bhagat Singh’s writings in any real sense. Moreover, although Bhagat Singh is associated with violence, his position changes, and there is no explicit meditation on the redemptive power of ‘killing the colonizer’ as we see articulated in Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. It is enough to note the continuities, and indeed the differences, between Bhagat Singh and the later Fanon, but Bhagat Singh should be analysed on his own grounds and in his own context, without the need to attach him to another, such as the ‘Indian Che’ or the ‘Indian Lenin’. That does not explain why he is unknown in the West, and nor is it to excuse it, but it is to emphasize how it is all the more important that this lacuna be rectified. One way to do this is to capture the essence of Bhagat Singh in his scattered and fragmented writings, in an attempt at intellectual reconstruction, so that alternative ways of thinking about his importance can be brought out.

Is this an exercise worth conducting? Yes, it is. Why? Because this mass heedlessness, absent-mindedness and inattention to the facts have obscured the full story of how Independence was achieved in India. Some Indian historians have recognized this, which is why Navtej Singh has referred to it as one of the ‘myths’ that are ‘widespread in bourgeois historiography’, that ‘Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, with the methods of non-violence and peaceful non-cooperation and civil disobedience, were instrumental in achieving India’s independence from the much-hated British Raj’. In his recent book on Har Dayal, who set up the Ghadar Party (i.e. ‘rebellion’ party) in San Francisco on 1 November 1913, in what he describes as ‘the largest international anti-colonial resistance movement’, Bhuvan Lall says of Bhagat Singh that he of all people had through his actions ‘redeemed and somewhat exceeded the anticolonial objectives of the Ghadr of 1857 and the Ghadr movement in California’. How did Bhagat Singh manage to do that?

First, Bhagat Singh drew from a far wider and deeper source of influences for his convictions than Gandhi ever did when he refers to actions of men such as Washington and Garibaldi, Lafayette and Lenin. This is how Bhagat Singh became the ultimate rationalist in the Indian revolutionary struggle. What distinguished him from other revolutionaries of the time was how, having started off life in the burning embers of insurgent Lyallpur and Lahore, his political development was ultimately refashioned, remoulded and refined by the vast array of international radical literature into which he immersed himself and imbibed right until the very moment of his hanging. He read not only Marx, Engels and Trotsky but also Thomas Paine, Upton Sinclair, Morris Hillquit and Jack London. He went on to read Victor Hugo, Dostoevsky, Spinoza and Bertrand Russell. Classical works were not overlooked so he also read John Stuart Mill, Thomas Jefferson, Kautsky, Bukharin, Burke, Lenin, Thomas Aquinas, Danton, Omar Khayyam, Tagore, N.A. Morozov, Herbert Spencer, Henry Maine and Rousseau. There is also his famous Jail Book, which came to light in 1974, of which Moffat writes that it ‘includes fragments copied from the work of some seventy different authors and which can be read in a myriad of ways, emphasising the passages on Marx rather than those on Rousseau . . .’ and where one can see ‘Bhagat Singh’s appreciation of Byron and Tennyson or his interest in natural law’.

Second, he believed in personal sacrifice for the attainment of his ideals, including having to give up his life if necessary. Prison gave him the opportunity to read voraciously. So much so that it is said that he wrote four books in prison which were lost after they were smuggled out. A letter written from Lahore Central Jail on 24 July 1930 to Jaidev Gupta, who was a close school friend from boyhood days, implores him the latter to ‘take the following books in my name from Dwarkadas Library’ and have them sent to him through his younger brother, Kulvir, by the following Sunday. The range of the books asked for is astonishing:

‘Militarism (Karl Liebknecht)

Why Men Fight (B. Russell)

Soviets at Work

Collapse of the Second International

Left-Wing Communism

Mutual Aid (Prince Kropotkin)

Fields. Factories and Workshops

Civil War in France (Marx)

Land Revolution in Russia Spy (Upton Sinclair)’

To this list, Bhagat Singh added ‘one more book from Punjab Public Library: Historical Materialism (Bukharin)’ and asked ‘if some books have been sent to Borstal Jail’ because ‘[t]hey are facing a terrible famine of books’ as ‘[t]hey have not received any book till now’. He rounded off by demanding, ‘Also send Punjab Peasants in Prosperity and Debt by Malcolm Lyall Darling’.

Bhagat Singh’s comrade Shiv Verma said of him, ‘No other revolutionary struck such deep rapport with the awakening people, no other became so endeared to the common people and youth as Bhagat Singh did.’ One reason for this was that ‘[a]s an intellectual Bhagat Singh was far superior to any of us’. For this reason, Navtej Singh writes that ‘he saw further than his comrades’ so that ‘it was at his suggestion and insistence that the word socialist was added to the name of the HRA, and the ideas of socialism, formulated in greater depth . . .’

Nevertheless, the extent of what Bhagat Singh wrote, from the time that he was taken prisoner on 8 April 1929 to the time that he was executed on 23 March 1931, remains contested. Indeed, it has entered into the realms of a make-believe world, populated by conjecture, supposition and even fantasy, to such an extent that it has today acquired a fabled and mythological life, all of its own. There is a reason for this. Take his four legendary books. They have never been found. But Shiv Verma, who was in jail with Bhagat Singh, confirmed later as an editor of Bhagat Singh’s selected writings that four books were written by the revolutionary. Chaman Lal, who has written most extensively about this matter, is circumspect, observing, ‘It is not clear if Verma actually read or saw these manuscripts or simply heard Bhagat Singh saying that he is working on them.’ Nevertheless, what is undoubtedly maintained by Chaman Lal is that ‘clearly Bhagat Singh did write something, and what he wrote was smuggled out of the jail by Kumari Lajjawati of Jalandhar’. So the well-settled view appears to be that, after he toiled away to complete his writings, some of them were secretly whisked out of prison into the trusting hands of Kumari Lajjawati, who was after all the secretary of the Lahore Conspiracy Case Defence Committee as well as a renowned Congress activist. She had been visiting the Central Jail in Lahore frequently to ensure that the Lahore conspirators were given such legal assistance in their defence as was possible. She is even said to have tied a ‘rakhee’ (a talisman that celebrates brotherhood and love) on Bhagat Singh’s wrist. The bundle of documents that had been handed over were shown by Lajjawati to the editor of The People, Lala Feroz Chand, this being the newspaper founded by Lala Lajpat Rai.

At any rate, this is what Lajjawati appears to have said when she was interviewed for the oral history archive of the Nehru Memorial Museum & Library. The disclosure to Lala Feroz Chand of the bundle of documents enabled the publication of one of the writings of Bhagat Singh, namely, his celebrated, ‘Why I Am an Atheist’, on 27 September 1931. This was designed to coincide with what would have been Bhagat Singh’s twenty-fourth birthday. Indeed, further extracts were also published and these included Bhagat Singh’s ‘Letter to Young Political Workers’. However, the bundle of documents has never been found. The reason for this is that Lajjawati herself passed them over to Bejoy Kumar Sinha in 1938, after he had served his sentence of transportation for life in the dreaded Andaman Islands following his trial with Bhagat Singh in the Lahore Conspiracy Case. He passed them over to another friend, who wasted little time in destroying them as he feared being raided by the police. In the words of Chaman Lal, ‘The loss of these invaluable documents must surely rank as one of the great tragedies of the period.’ That a bundle of documents existed appears to be the considered view of Chaman Lal for as he explains,

Bhagat Singh’s father was keen to acquire the papers, or at least to see them. Lajjawati refused to give them to him, purportedly on Bhagat Singh’s own instructions. We must consider ourselves fortunate that some member of his family, probably Kulbir Singh, managed to retrieve Jail Notebook . . .

This throws up a couple of questions. First, if the bundle of documents, smuggled out of prison by Kumari Lajjawati was eventually destroyed by an unnamed friend of Bejoy Kumar Sinha, with only ‘Why I Am an Atheist’ and ‘Letter to Young Political Workers’ being published, how can we know for sure that four named book manuscripts also specifically existed? Second, the fact that the two named articles were indeed published from this smuggled bundle of documents by Lala Feroz Chand does suggest that something was in all probability written during his two years in jail, although it is unlikely that he would have had the time to complete four books in their entirety. This much is fairly recognized by Chaman Lal, noting of Bhagat Singh how ‘during this time, he was engaged in agitation inside the jail, as well preparing for the trial’. This being so, ‘it seems unlikely that he could actually have finished writing four full-fledged books, even considering his enormous energy and willpower’. Nevertheless, the belief that a treasure trove of lost Bhagat Singh documents existed refuses to die. This is perhaps best encapsulated in the journalist Bhupendra Hooja’s lament that ‘the vacuum of these precious manuscripts’ is something which ‘no amount of literature on or about Bhagat Singh . . . can fill’. The result is, as Moffat points out, that at the very least the existence of ‘a fragmented assemblage of personal notes’ is something which today ‘fuels a narrative of unconsecrated potential, opening space for rumination’. Yet, if it were possible so to do, what would a consecrated potential look like? This is the perpetual question to which an answer must be sought.

Excerpted with permission from Bhagat Singh: A Life in Revolution, Satvinder Juss, Penguin India. Read more about the book here and buy it here.