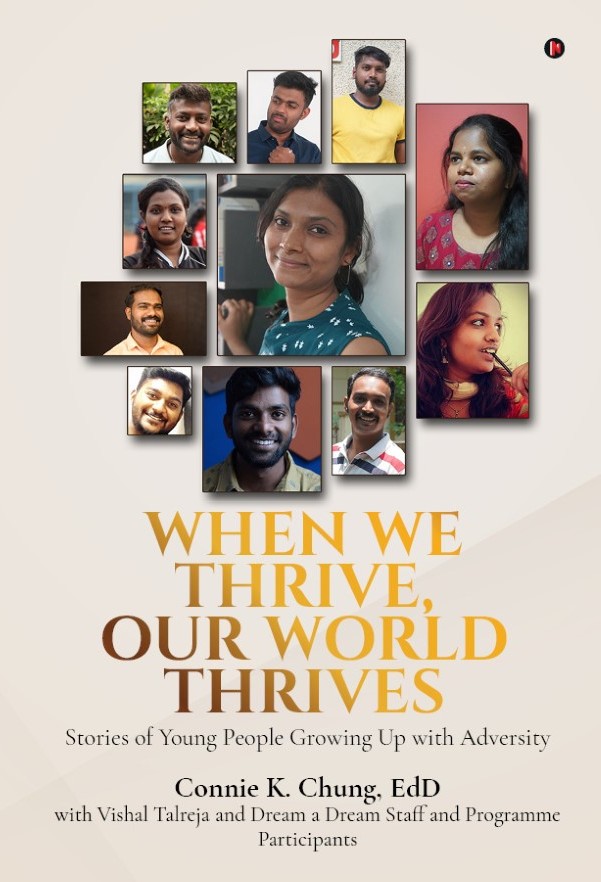

The book “When We Thrive, Our World Thrives” by Connie K. Chung with Vishal Talreja is about the graduates of Dream a Dream.

Since 1999, Dream a Dream has gained the attention of Indian and global communities as a leading education non-profit that is cracking the code on how to support young people with backgrounds of adversity to thrive, realise their potential, and become leaders who will shape our collective future.

The book centres on moving, personal stories of young people and what it means to grow up with adversity and thrive. It weaves in research about positive youth development and best practices of the globally recognised life skills programme developed by Dream a Dream; it also chronicles Dream a Dream’s growth and development as an organisation.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

Revanna Marilinga was born in a small village in the Mandya District, a largely agricultural area, some 70 miles away from Bangalore. His parents worked for daily wages, so even as a toddler, he was left at home by himself, as an only child. He tried and failed twice in the school selection process. The school headmaster and teachers would visit his village to ask parents about the ages of their children. If the parents did not know the age of the child, the school authorities would ask children to touch their ears. They believed that those who could touch their ears when asked were at least five years old and could attend school, but Revanna could not. Thus, Revanna associated the feeling of failing with school, even before he set one foot in a classroom.

When he did make it to school after the third time of taking the test, it was an even bigger disappointment. Not only did his school not allow him to play, but there were active restrictions that he was not used to at home. While at home, he could play, eat, or sleep. But at school, all he was allowed to do was to sit and listen to the teacher.

Without any prior formal learning experiences nor preparation, Revanna felt “very weak” and “totally ill-prepared to learn,” he recalled. “In the third standard, we were expected to write sentences, but when I was unable to recognize letters, how could I write sentences?” he reflected. The response from the school authorities was not to provide him with extra help, but beatings from the teachers when he was unable to answer their questions.

Revanna decided that between his apparent inability to learn and the daily painful, tear-inducing beatings from teachers, that “school was not for me.” When he informed his mother that he would not continue his education, his parents said that not going to school was not an option. To his parents, sending him to school was the only way to ensure that they had regular child care so that they could focus on working and earning their livelihood. His parents insisted that he continue to attend school.

Revanna coped as he could, by walking to school, putting his bag inside the classroom, then running out to play in the field by the school and then returning home by lunch time. He maintained this routine until the end of the academic year, when his parents found out that he was not eligible to take the final examination because of his poor attendance. When the principal told his parents about Revanna’s absences from school, his parents were in disbelief at first. Then they insisted that he attend school, no matter how painful the punishments were. Perhaps his parents wanted him to have more choices than they did, by attending school, or perhaps they thought that the physical punishments were no less ordinary than what they themselves experienced in school. When Revanna tried to insist that he could help them with their work instead of enduring daily beatings on his knees at school, his parents did not listen to him.

Running Away to Bangalore

Disappointed and angry with his parents for not being sympathetic to his physically and psychologically painful experiences at school, Revanna snuck on a passing train to Bangalore, thinking he could find a job in the big city. He was just eight years old. He looked for jobs in different places, but no one would hire him. As he sat in the Bangalore railway station, crying, staff members from BOSCO (Bangalore Oniyavara Seva Coota), an organisation that worked with street children and provided them with shelter and basic education, found him. Founded in 1980, Bosco takes in about 650 children from the street each year in Bangalore. Revanna gave all false answers to their questions about his background because he did not want to return home and be forced to go to school. His goal was to find work and earn money to prove himself before returning home.

He found that at the shelter home, there were basically two groups; one group of children who attended school, and another group who chose to work. He also found out that he had to be at least 14 years old in order to work, and that he could not even work part time until then. He stayed in the shelter home, not even attending school. As he observed the children going to school, however, he noticed that those children participated in activities outside of school. Not only did they attend school from 8 o’clock in the morning to 4 o’clock in the afternoon, but they also went to cultural activities in the evenings and played sports. Wanting to go on field trips and play sports with them, Revanna finally overcame his fear of going to school and told the counsellors at Bosco that he wanted to go to school.

Discovering a Passion and Talent for Swimming and Learning Not to Give Up

When Revanna started going to school in Bangalore, he discovered his love for sports. Father Cyriac, the director of the Bosco Centre, firmly believed that sports could help the children at the centre. Bosco had partnered with different sports coaching academies for cricket and swimming and a partnership with Dream a Dream for field hockey and table tennis. Revanna tried cricket, but found he was not very good at it; he tried field hockey and found the same thing. He tried table tennis a couple of times, and also had no success. He remembered that throughout his many attempts at different sports, “there were no judgmental statements” made by volunteers and staff when he could not play well. He recalled, “When I failed hockey, nobody scolded me; no one beat me. When I failed cricket, though they had put more effort into coaching me than they had for other players, they did not express their disappointment. They gave me space to find a sport that was suitable for me.”

That process of trial and error in an environment that centred on him as a young person discovering his talents led Revanna to try swimming. Not only did he learn to swim but discovered that he was excellent at it. Revanna was selected with 24 other young people to be coached to learn how to swim every weekend by another Bosco organisational partner. After those sessions, he was thenselected to receive coaching every day for two hours, during regular school hours. He swam with the Basavanagudi Aquatic Centre for five years. Even with just a simple basic swim gear sponsored by the coaches that he found embarrassing to wear in front of others who were outfitted in more expensive and better developed gear, Revanna ended up being selected to travel and represent the club and the state of Karnataka in swim competitions for 5 years.

In order to continue to participate in sports, he kept up his studies and attended school. He participated in other Dream a Dream activities, such as Fundays and Outdoor Adventure Camps, learning life skills along with his classmates, and having a fun time playing. He recalled that he gained confidence, such as being more comfortable speaking in front of others, not only in his native language, but also in English. For example, he rejected at first an opportunity to co-host Dream a Dream’s annual celebration event, because he was insecure about his ability to speak English in front of others. But Dream a Dream staff did not give up and persuaded him to prepare by reading from a script. They practised with him for a week. By the time of the event, he was able to speak in front of donors and other stakeholders.

Revanna recalled, “I was so confident that my stage fear and fear of speaking English disappeared. It changed my life.” With his English skills that he was continuing to work on even at the time of this interview, at age 29, Revanna hosts visitors from abroad, has spoken at multiple conferences and has led multiple teams from Dream a Dream to Wales, Brazil and elsewhere. With all the support that he received while trying different sports until he found swimming, and the other guided challenges that Dream a Dream helped him to overcome, Revanna said, “I learned not to give up.”

Excerpted with permission from When We Thrive, Our World Thrives: Stories of Young People Growing Up With Adversity, Connie K. Chung with Vishal Talreja and Dream a Dream Staff and Programme Participants, Notion Press. Read more about the book here and buy it here.