A lot of fantastic books have come out this year, and delving into these excellent works in both fiction and non-fiction truly offers us a precious opportunity to expand our horizons. To get to know about some of the best reads this year, I asked authors, translators, book critics, and people connected with the publishing industry about the books that have impressed them. Here are some of the best books published in 2021 to date, as read and nominated by them, in no particular order.

Paul Melo e Castro

An excellent book I read this year was Jenni Fagan’s Luckenbooth. Set in the eponymous Edinburgh tenement – a residential building divided up into flats so common to Scottish cities, and which set them off from their English counterparts – the novel follows various inhabitants over nine decades, starting in 1910, as the world buckles and warps outside and within. One critic compared it to Georges Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual – another book I love – and there are certainly parallels not just in architectural structuring but sheer range of imagination. One thing an audience from afar might appreciate is how Luckenbooth goes through the gears of Scottish literary fiction, from touches of gritty social realism to Gothic shocker. It’s a world in a building and, at a stretch, maybe a literature in a book.

Paul Melo e Castro lectures in Portuguese and Comparative Literature at the University of Glasgow. He is the translator of the book ‘Monsoon’ by Vimala Devi.

Trisha De Niyogi

These have been my favourite reads this year –

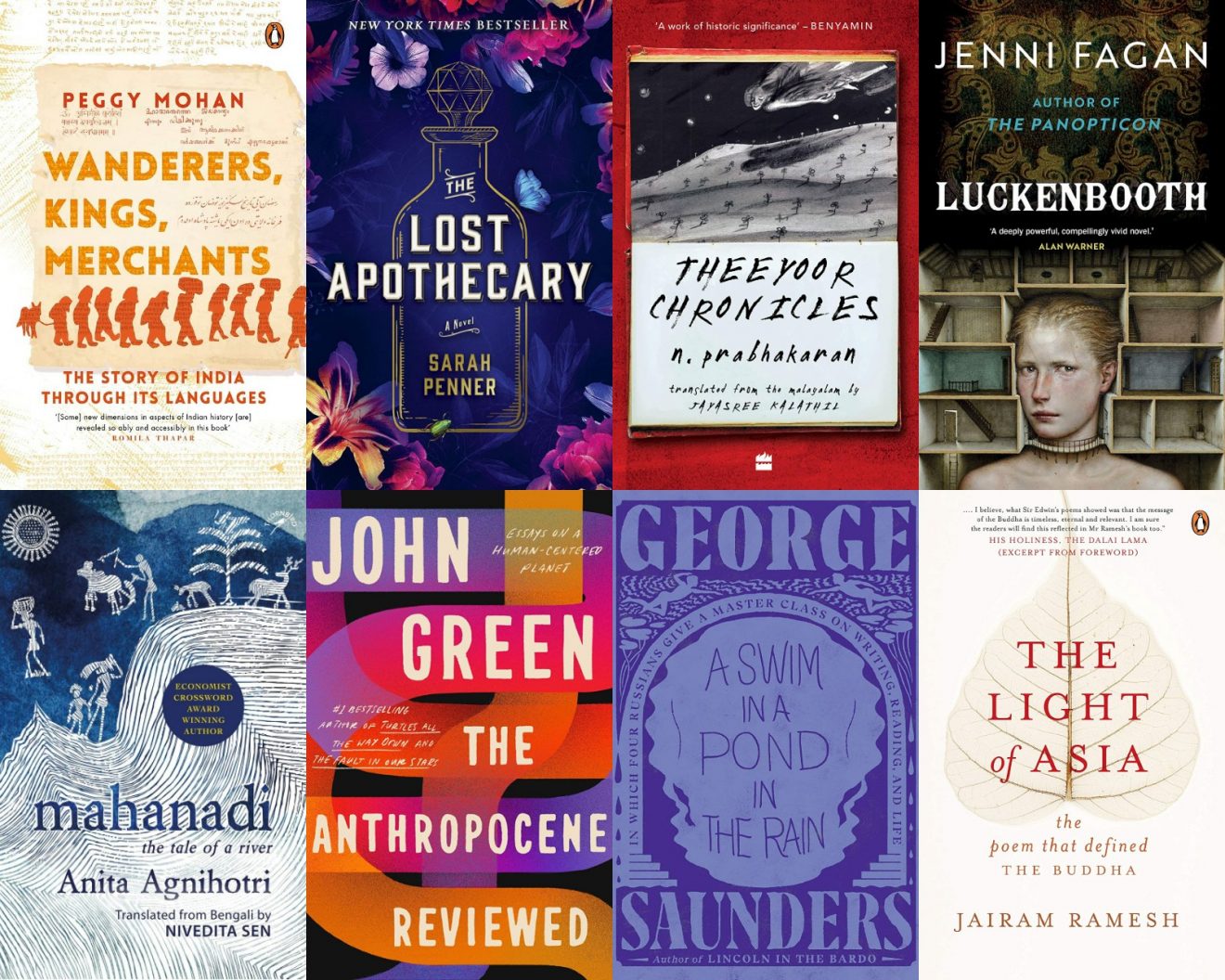

Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India through Its Languages by Peggy Mohan: Over the last couple of years, I have been reading and working actively on Indian languages and translations; and this timely book addresses my question of how India came to have so many languages and prods me to think – on why standardization of the nation’s tongue is an insipid argument. While the book also addresses Indian history through the vehicle of linguistics, what appealed to me the most were the details about the gender discrimination in languages, for instance, the use of Sanskrit by men and a local Prakrit by women, as found in Kalidasa’s Abhijnanasakuntalam. The book draws attention to the fact that languages are dying and the reasons behind it through an in-depth study, in a rather accessible format, even though initially it may not come across as an easy read.

The Lost Apothecary by Sarah Penner: In the second lockdown, while anxiety levels were skyrocketing, this poisonously entertaining read helped me to break a month-long reading slump. Set in London, the book seamlessly floats between the past and present, revealing heartaches and dreams through the eyes of the women characters. Penner’s reference to motherhood and impending womanhood also compelled me to turn the pages till the very last sentence, even though it was slightly slow in the beginning.

Mahanadi: The Tale of a River by Anita Agnihotri: As I read the manuscript of a monograph on Sundarlal Bahuguna by Vandana Shiva, the part on Tehri Dam prompted me to pick up the book Mahanadi: The Tale of a River originally written in Bangla by Anita Agnihotri and translated into English by Nivedita Sen, before it is released on 15th July. This unusual chronicle of one of the largest rivers of India casts an insightful light on some of the least developed, poverty-stricken regions of Chhattisgarh and Odisha where the inhabitants struggle to eke out a living on the banks of the mighty Mahanadi. Living on the fringes of society, these people and their way of life have mostly remained unknown to the rest of India. This socially relevant novel is perhaps one of the most important releases in this year as we continue to debate on the paradox of development and environment.

Trisha De Niyogi is the director and COO of the publishing house Niyogi Books.

Sayantani Dasgupta

In the preface of his hybrid memoir Antiman, the Caribbean writer Rajiv Mohabir says, “If I have offended anyone’s sensibilities or their versions of these stories, I am not sorry.” From that very sentence, you know you are in the hands of a solid storyteller, one who will respect your time and engagement with his writing, who will not condescend to you or fill you up with pointless sentimentality. My favourite aspect of Antiman, however, is not how fearless it is, but the way it delivers surprises on every page. There are chapters in the form of journal entries, poems, verses in Guyanese Bhojpuri interspersed with those in English and Sanskrit, along with pointed and relevant questions about India, Indian-ness, and who is a “real” Indian.

Sayantani Dasgupta is a professor of creative writing. Her latest book, ‘Women Who Misbehave’, is out now from Penguin Random House.

Jenny Bhatt

Picking favourite reads is always so tricky because there are always more books than space to discuss them. So I’d like to spotlight books in literary translation because they often don’t get as much attention. I believe that some of our richest South Asian literature continues to be written in the regional languages. And a lot of our amazing ancient and pre-21st century literature remains untranslated because of various market-driven reasons. So, as readers, we can all do our bit by reading and asking for more such translations as a way of preserving and elevating our own literary traditions.

This year has given us so many terrific books from regional languages into English. I’ve appreciated Theeyoor Chronicles by N. Prabhakaran and translated from the Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil. It’s a fascinating hybrid genre novel with history, mythology, politics, fiction, all in one. A feat of writing, too, because of how it uses different forms (letters, factual documents, oral anecdotes, etc.) in its narrative. Khwabnama by Akhtaruzzaman Elias, translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha, is a historical novel set during the 1940s and it has magical realism, folklore, and more. It’s both broad and deep in scope and, though it would fit the growing “Partition novel” sub-genre, it’s so much more than that. And, finally, I love the work being done by the Murty Classical Library of India and have just read Lilavai by Kouhala, translated from the Prakrit by Andrew Ollett. This is a ninth-century poem centering on three women but featuring a polyphony of voices. It’s got mythology, folklore, romance, female desire, and more. And I love that it’s an ancient text centering women, which is not something we’re used to reading.

Jenny Bhatt is a writer, literary translator, and book critic. Her literary translation, ‘Ratno Dholi: Dhumketu’s Best Short Stories’, is out now from HarperCollins India.

Deepankar Aron

My favourite read this year has been The Light of Asia: The Poem that Defined The Buddha. This scholarly treatise by Jairam Ramesh on a revolutionary poem written by the indologist, Sir Edwin Arnold in 1879 introducing Buddha and Buddhism to much of the ‘western’ world, gave me an opportunity to read the original epic poem as well, which much to my surprise had eluded me all these years. While explorers and scholars like William Jones, Alexander Cunningham and James Princep did much to re-discover Buddha and the Buddhist heritage in India in the 19th Century, it was this beautiful poetic rendition of Siddhartha’s transformation into Buddha which ignited the minds of several Nobel laureates and leading luminaries of the day like Gandhi, Vivekananda, Tagore, Ambedkar, Andrew Carnegie Mellon and his wife Louise Whitefield, King of Siam (Thailand) and many more. As Jairam brings out in this unputdownable book for any enthusiast who is more interested in the humanity of Buddha than his divinity, the poem by Arnold not only illumined the lives of people exposing them to a very scientific basis of spirituality that lies behind Buddhism, it also engineered social movements in India demanding no discrimination on the basis of caste. The poem stirred the famous monk from Sri Lanka, Anagarika Dharmapala, the co-founder of the Mahabodhi Society of India, to initiate a great archaeological movement that outlasted even him, spread over 67 years culminating on 28th May 1953, eventually bringing the famous Mahabodhi temple in Gaya into the administrative fold of a Joint Committee of Buddhists and Hindus, when the control of the temple had gone to Shaivites in 18th century following a Mughal grant.

The book is as much a biography of the poem as it is of the author, Sir Edwin Arnold. This poem as well as the other one Arnold wrote on Gita called the ‘Song Celestial’ had a profound impact on Gandhi. Jairam beautifully brings out how the first introduction to Gita for Gandhi was through this very book, when two Theosophist brothers Bertram and Archibald Keightley invited Gandhi to read ‘Song Celestial’ with them, and he mentions Gandhi candidly admitting that until then, he hadn’t read Gita!

It is no wonder then that this epic poem has been translated worldwide into 30 languages. In my own readings, indeed, there is not a single compact, beautiful source like this poem that makes one immediately familiar with the life of Buddha and what shaped his mind, culminating into that wakefulness that some call enlightenment, which Buddha himself said is no magical thing and that it can be attained by any and everybody, and that each is free to experiment and find his way! One has to be thankful to Jairam for underscoring the timeless impact of the epic poem and its continued relevance in the 21st Century, when the world more than ever before needs a reiteration of our ‘Oneness’, of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’.

Deepankar Aron is an Indian Revenue Service officer. His latest book is ‘On the Trail of Buddha: A Journey to the East’.

Priyanka Sarkar

My favourite reads this year are –

We Free the Stars by Hafsah Faizal: This is the second part of a very satisfying duology in the fantasy-romance genre about friendships, betrayals, kinship, power, corruption and what it means to be a ruler.

The Begum and the Dastan by Tarana Husain Khan: A layered story about the power of women and their resilience. There are three stories that mirror each other and you root for all the heroines.

Unravel the Dusk by Elizabeth Kim: This is again the conclusion of a fantasy-romance duology. A headstrong, ambitious heroine who has to fight the literal demon inside her, this one is again about inner strength. The climax could have been better though.

Priyanka Sarkar is a translator, editor and writer. She is the translator of the book ‘Bhairavi’ by Shivani.

Prachand Praveer

Largely Hindi literature is dominated by partisan ideologies and often blamed for substandard works lacking any originality or valuable contemplation. Contemporary renowned philosophy scholars, Dr. Ambikadutt Sharma (Sagar University) and Dr. Vishwanath Mishra (BHU), have produced a valuable book, Hannah Arendt: Himsa ka Utkhanan (Hannah Arendt: Excavation of Violence), in the light of ideologies of 20th century major German political thinker Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948). The author duo contemplates about violence inherent in social structure in the light of two different ideologies: first is in the line of European modern political philosophies consisting of those of Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and Karl Marx (1818-1883); and the second, the non-violent political philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi and Hanna Arendt.

While relating violence with subtle dissatisfaction in the modern society with its pervasive inequality, and relating to the idea of labour and justice, we find that violence has only increased. Many ideologies such as Totalitarianism, Marxism, Utilitarianism and even feminism either endorse violence or have no answer to proliferating violence. The author duo finds the fundamental problem with Social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), the notion of ‘survival of the fittest’. Unless a careful distinction is made between men and animals, modern times are doomed to be violent.

Hannah Arendt demarcates human activities into labour (physiological efforts to sustain life), work (activities related to fulfil material needs), and action (activities related to higher goals in life while maintaining diversity). While Mahatma Gandhi refuses any such distinction as he believes that such efforts will lead to class distinction and special privileges which will further lead to violence, Hannah Arendt argues that the very substance of violent action is ruled by the means-end category whose chief characteristic, if applied to human affairs, has always been that the end is in danger.

Hannah Arendt opines that men seek endurance in time and novelty. For achieving both, the social being of men is of paramount importance, in other words, society is prior to the self. It should be noted that she prefers to refer to humans as ‘they’ instead of ‘he’; similarly she uses ‘Men’ instead of ‘Man’. For Hannah Arendt, power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert. Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only so long as the group keeps together.

However, totalitarian regimes depend on an atomist society where they have more prohibitions on civil life. The book examines various political philosophies, religious traditions (Abrahamic vs Brahmic), along with various socio-economic models during the investigation and relates those concepts in Indian classical philosophical terms. The writer duo finds hope in Gandhi’s vision and forces us to rethink the way modern ideologies have reluctantly accepted violence as the solution of violence.

Prachand Praveer is the author of the book ‘Cinema Through Rasa: A Tryst with Masterpieces in the Light of Rasa Siddhānta’.

Akshat Tyagi

My favourite book published this year is The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green. I did not discover Green for his young adult fiction, in fact, this reputation only provoked doubts in the smug snob within me. I grew out of this dumb judgment the first time after listening to a podcast by the name same in which he reviews random objects or phenomena of human-centered age like the Notes App or the Non-Denial Denial or Sunsets on a five star scale. In his affable anxious voice, he would meander around the embedded complexity and unnoticeable beauty of weird things. I waited a long while for this book and it’s easily one of the most charming non-fictions I’ve read in a while.

The second book I loved this year was George Saunders’ A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. Imagine learning the art of writing short stories from one of the greatest writers of our times and with the best works of four Russian writers as your course book. It’s a detailed walkthrough about writing better fiction, though it also turns into a guide about empathy, attention, and patience, as most of life is. If you wanted the pleasure of Stephen King’s On Writing but also something more useful, this would surely help. It grows one into a slightly more honest reader who dares to ask Tolstoy questions and probes beyond the superficial.

Akshat Tyagi is the co-author of the book ‘Now That We’re Here: The Future of Everything’, out now from Penguin Random House India.