The Building Itself: Masjid-i Shah and Its Decoration

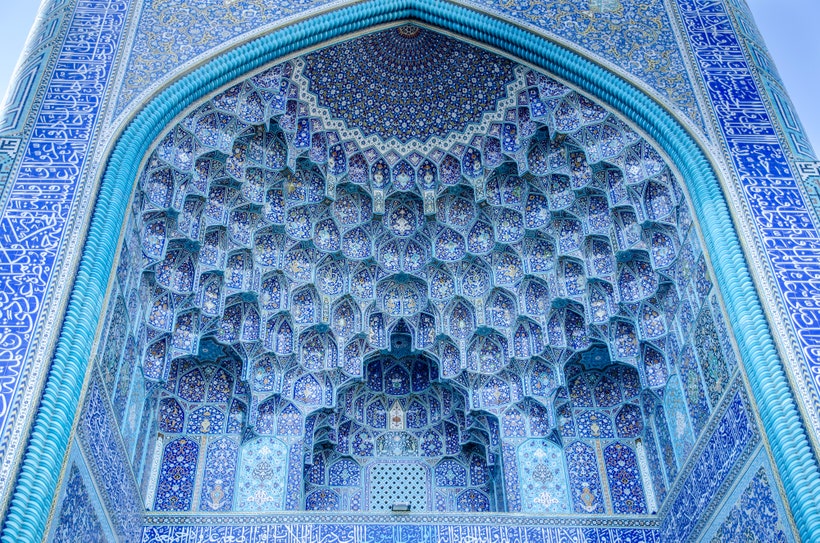

The Masjid-i Shah’s grand entrance portal (iwan) measures 27m in height and is capped by a muqarnas filled semi-dome which rises high above the roofline of the two-storey Maydan and is flanked by two minarets. Framed by turquoise, triple-cable ornament, the portal is clad in tile mosaic and contains an inscription band of white thuluth calligraphy with a dark blue background, which stretches around the three sides of the portal. In her survey of the inscriptions of the Maydan-i Shah, Sheila Blair notes that this foundation inscription above the mosque’s grand portal ‘specifies that the building [bina’] of this congregational mosque [masjid al-Jami’] was ordered through private funds of the Shah and dedicated to the rewards of his grandfather Shah Tahmasp’. Moreover the foundation inscription is signed by Ali Reza al Abbasi and dated to 1025 /1617. A noted calligrapher, Ali Reza replaced Sadiki Beg as the chief librarian of the Kitabkhane around the time the mosque was built and his workshop probably provided many of the patterns and artists for the calligraphic and decorative compositions for Shah ‘Abbas’s building projects.

After passing through the Mosque’s atrium, which is a prolongation of the grand entrance portal, there is an immediate but almost imperceptible change of direction to the right. The change of direction is due to the Maydan square being orientated according to the four cardinal points, whereas Makkah lies to the southwest of Isfahan. To accommodate the shift in direction between the cardinal points and the mosque that needed to align its qibla wall to face Makkah, the axis of the mosque diverges from that of the gate by almost 45 degrees. The purpose for this low gloomy passage leading into the dome chamber becomes evident, for it is with a sense of heightened anticipation that the mosque’s courtyard is entered. Lowness gives way to soaring height and the light streaming into the open-roofed courtyard dispels the gloom. Following the traditional Persian mosque plan, the mosque’s courtyard (50 × 67m) is surrounded by a two-story arcade on four sides. A large iwan is at the centre of each arcade and a large domed sanctuary is located beyond the southwest iwan, facing the direction of Makkah. The side iwans also lead to domed sanctuaries, which are flanked by rectangular rooms functioning as winter prayer halls. These halls are covered by eight domes and connect to two rectangular arcaded courtyards serving as madrasas, which were designed by Sheikh Baha’i and later used by him for his teaching. Both the entrance portal iwan and the main sanctuary iwan, where the qibla mihrab is situated, are flanked by a pair of cylindrical minarets. These minarets are totally clad with tile mosaics of epigraphic elements such as La illaha illa Lah (There is no God but God). On top of the minaret’s upper area runs an inscription band in white on a blue background, marking the beginning of three tiers of muqarnas units, which appear to hold the minaret’s roofed balcony.

The tiles that adorn the seventeenth-century Masjid-i Shah in Isfahan represent one of the most outstanding examples of colour use on a grand scale in the world. Almost every surface of the interior and exterior of the huge Safavid complex is covered in brightly coloured tiles. The apogee of colour production is embodied in the saturation and intensity of harmonious colours found on the Masjid-i Shah, which Pope describes as the

culmination of a thousand years of mosque building in Persia. The formative traditions, the religious ideals, usage and meanings [and the] ornamentation are all fulfilled and unified in the Masjid-i-Shah, with a majesty and splendor that places it among the world’s greatest buildings.

Thus the building bears witness to a tilemaking tradition that possessed a highly sophisticated knowledge of the laws of colour from technical and aesthetic perspectives.

Despite some of the tileworks being replaced in the 1930s, the Masjid-i Shah has changed little from when it was competed in around 1630. Here glazed tile revetment is exploited to its fullest with both its interior and exterior walls fully coated in magnificent colour. Colour is applied on such a massive scale here that it is difficult to absorb all at once. The tiles both delineate and accentuate the different patterns and parts of the building and are fluid and adaptive in both scale and character. The polychrome tilework that clothes the domes, wall panels, arches, muqarnas, and portals can all be admired individually from up close as well as from afar. When viewed from a distance, Welch observes,

This architecture creates images of dazzling beauty, where reflecting surfaces catch light in brilliant colour in a way strikingly similar to Safavid textiles and silk carpets. Structures become indistinct, even visually unimportant, and the repetitive surfaces of the glistening tiles become translucent visions, disembodied and ethereal.

The tilework also accentuates the building’s shape, with separate but united colour schemes lending movement to the architectural stresses and forms in the structure. In his contemporary account of the mosque, the court chronicler Iskandar Beg Munshi describes the mosque as a ‘paradise-like place of worship’, comparing it to the ‘nine-arched vault of heaven’ and the ‘Bayt al-Ma’mur’. Indeed, emulating the Qur’an’s symbolic description of the lush, fertile abundance of paradise, this building displays a vast presentation of brightly coloured floral decoration that is both abstract and imaginative. In one beautiful passage, Pope suggested that the ornament used in the mosque is an example of the Islamic attraction to flowers, which he describes as ‘poetic’ and also reverential.

Colour in the Building: Haft Rang (Seven Colours)

This section introduces the principal tile technique used to decorate the Masjid-i Shah including technical aspects such as its makeup and application, its history in ancient Persia both in relation to its technique and the cultural and conceptual associations with the heptad (number seven) and seven colour traditions. The aim here is simply to introduce the medium of the artwork (Masjid-i Shah) that helps inform the approach employed in this research.

Whilst the mosque’s minarets and entrance portal are decorated in tile mosaic, a slow and expensive process in which pieces are cut from monochrome tiles and arranged to create intricate designs, most of the mosque surfaces employ a technique known as Haft rang (Haft seven, rang colours). This technique is essentially an overglaze polychrome used for ceramic decoration wherein the craftsman composes the same shapes as seen in tile mosaic by painting directly onto a square tile, and then pursues the same pattern across the second tile, and then onto the third tile, etc, until the frieze is complete. A pattern may be made up of four or eight tiles and then repeated to complete friezes of repeating patterns made from numerous tiles. From discussions with modern master craftsmen at the Negin tile workshop in Isfahan, the Haft rang technique has remained largely unchanged and is still being practised in the last remaining tilemaking workshops today. According to observations of craftsmen at the Negin workshop, the technique is relatively straightforward. It begins with the transfer of an entire design to an assembly of square tiles by placing a transfer paper pricked with the particular design and pounced with charcoal through the holes. Once the transfer paper is removed, the faint carbon outline is then traced over with a mix of manganese and a greasy substance, which traditionally was animal fat or linseed oil. The craftsman then applies the water-soluble glazes that constitute the Haft rang colours within the areas delineated by the greasy outline. When heated in the kiln, the glazes do not run together because they are separated by the greasy manganese substance, which evaporates leaving a matte line that then outlines the coloured patterns.

The term Haft rang was first recorded by Abu’l Qasim in his ceramics treatise in the fourteenth century which describes a technique known today as minai glazed ware or overglaze polychrome decoration. In 1888 the term was used by the Qajari potter, Ali Muhammad Isfahani in Tehran, who recorded Haft rang methods and materials in his treatise On the Manufacture of Modern Kashi Earthenware Tiles and Vases. In interviews with craftsmen in Isfahan, Barry has found that this designation and practice of Haft rang is still used today in Iran as well as other central Asian countries. In all of these methods for glaze application, a dark-coloured line, normally black, is used to delineate the various coloured glazes. This is the reason why Haft rang is often compared to another polychrome technique called in Spanish cuerda seca (dry cord). Cuerda seca here refers to the black line which is used in both the techniques of Haft rang and cuerda seca for separating coloured glazes.

Interviews conducted with contemporary craftsmen and academics in Isfahan today revealed the term Haft rang refers to the traditional designation of seven colours and has correspondences to various phenomena in traditional Persian and Islamic culture such as cosmology, geography, etc. Whilst a review of the relevant literature found no definitive explanation for why the tiles of the mosque were named as such, since the colours do not always constitute seven colours, other scholars have suggested that the use of the word seven (haft) in Haft rang simply means ‘many’. This interpretation was repreated by conservators from the University of Isfahan, who stated: ‘Seven is an important idea. Don’t take these things literally . . . For us, the number seven represents completeness, wholeness and the harmony of everything. Seven is a complete number. It is essentially about making sense of the universe.’ This view tends to support Annemarie Schimmel’s research into Islamic number symbolism that the number seven was revered by various ancient civilisations as a mystic device denoting periodicity, completeness and spiritual and mundane concepts. In her book, The Mystery of Number, she writes further that, because of its wide use, the number seven could become an indefinite round number meaning ‘many’. The entry on Haft in the Encyclopedia Iranica states that the sacredness of seven for the Iranians was enhanced from the Median period (678–549 BC) onward, partially due to contact with Mesopotamian culture, in which the heptad played a dominant role. Moreover, Schimmel points to a number of Persian treatises called Seven Spheres or Seven Climata which are about a whole range of subjects: ‘These Persian works are not, as one might expect, geographical studies but rather treatises on different kinds of literature, the seven in their titles expressing completeness.’

Excerpted with permission from Colour, Light and Wonder in Islamic Art, Idries Trevathan, Saqi Books. Read more about the book here and buy it here.