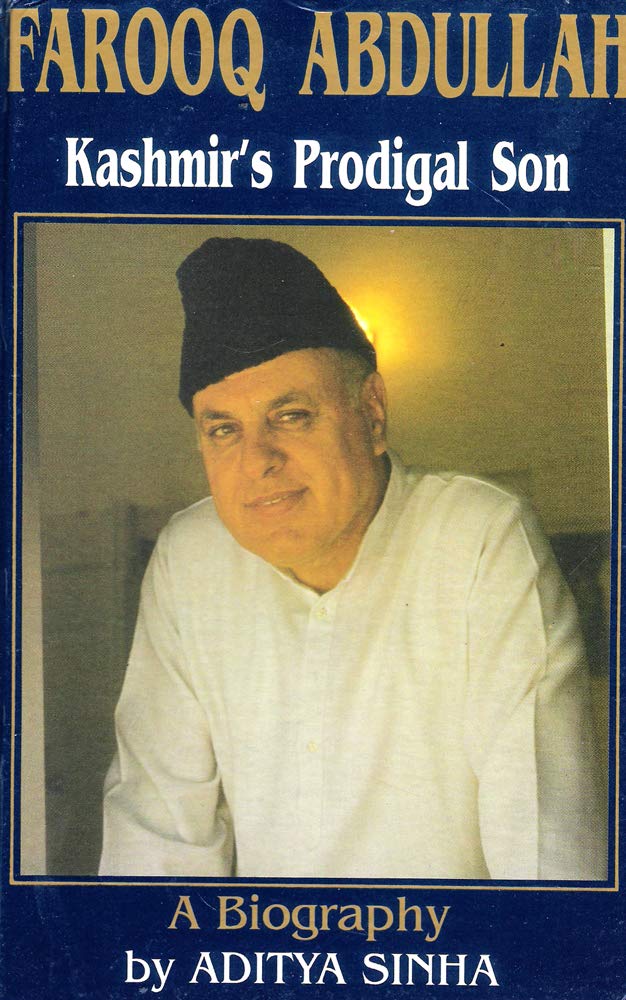

As Farooq Abdullah is set to walk free after over seven months of detention, we are reminded of his statement of 28 June 1989 made in context to his father Sheikh Abdullah, who had spent over a decade in jail.

Here is an excerpt from the book titled, ‘Farooq Abdullah: Kashmir’s Prodigal Son’, a biography by Aditya Sinha.

While out of power between July 1984 and November 1986, Farooq Abdullah apparently decided that he was not going to pursue politics the way his father, Sheikh Abdullah, had. He was not going to spend years on end in jail, and he was not going to wait for elections, only to be toppled again and again.

Farooq made his views clear at a Lal Chowk meeting on 28 June 1989: “…if you have in mind someone who ends up in jail, you can count me out,” he told party activists. “I am the last person to like being jailed. I like to play golf. “What am I going to do in jail? You may suggest that I read books to while away time, but I would not like to do that because reading puts pressure on my eyes.”

Yet, like any other politician on the Indian subcontinent, he was wanted be back in the saddle as soon as possible. He was clear, though, that his politics would entail little sacrifice, because he had decided to take Mridula Sarabhai’s advice, and be the kind of husband and father to his family that his own father had never been. In fact, Farooq was, above all, a family man, and he adored Molly and his four children: Umar (born 1970), Safiya (born 1971), Henna (born 1975) and Sara (born 1978). (Presently, Umar is married and works in a Delhi hotel; Safiya teaches in a Delhi school, Henna is studying at Cardiff in Wales; and Sara, the only one born in Kashmir and named by her grandfather, lives in London With Molly.)

Coincidentally, it was another well-known family man who played a significant role, in more ways than one in Farooq’s hasty return to power: Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The youthful Prime Minister, though politically naïve, had an endearing charm, and it was he who first attempted to apply a soothing balm to an angry Farooq Abdullah after the latter’s dismissal in July 1984. Rajiv, then still an MP, read in horror press reports about an extremely irate Farooq who threatened to “liberate India from the fascist and communal rule of Indira Gandhi”. Farooq was addressing a rally at the Mazaar-e-Shohda soon after his dismissal. At a public meeting in Rafiabad he accused Delhi of enslaving Kashmir and attempting to change the Muslim character of the state. He told a Mujahid Manzil rally that “Kashmir is for Kashmiris and anyone who thinks otherwise is living in a fool’s paradise”; and most damning of all: “I’m sick of repeating ad nauseam that I am an Indian and that Kashmir’s accession to India is irreversible. Why don’t the Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu or Maharashtra have to say the same thing?” he snapped in an interview to the Pakistani magazine Herald’.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi visited Kashmir on 27 October 1984, and she was disgusted with what she saw of G.M. Shah’s administration. It was corrupt, it was unpopular, and she realised that it had to go. She returned to Delhi, and told her son how she felt.

Rajiv, who was also one of the All India Congress Committee’s General Secretaries, secretly visited Farooq and had lunch with the former Chief Minister. It was a pleasant get-together, for Farooq was fond of Rajiv, and found him more straightforward than his late brother Sanjay.

During the meeting, Rajiv asked Farooq if he would mind meeting Indira Gandhi quietly, so that certain matters could be straightened out. Farooq was requested to come to Delhi. Despite all that had happened, and the ignominious manner in which Indira Gandhi had tossed him out, Farooq agreed.

The meeting was fixed. Farooq reached the capital for the meeting, which, however, got postponed and rescheduled for a later date. Meanwhile, a terrible tragedy occurred: on 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated.

When he heard the news, Farooq rushed over to 1, Safdarjung Road. Indira Gandhi’s body was still at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). Rajiv Gandhi was somewhere in West Bengal and efforts were on to trace him. President Zail Singh, who was abroad, was already on his way back.

Rumours were afoot that Indira Gandhi was still alive, although Farooq had heard that she had died on the spot. For a while Pranab Mukherjee was being projected as the caretaker Prime Minister, although the moment Rajiv arrived, it was clear who would hold that position. The funeral took place, and the new government fumbled to find its feet. Farooq returned to Srinagar.

With a new Prime Minister in the saddle, Farooq had to wait as Rajiv came to terms with his job and the other problems he had inherited from his mother. Nonetheless, Farooq got the ball rolling in 1985 itself, soon after Rajiv came to power, after general elections, and in statement after statement, in speeches and press conferences, Farooq kept urging Rajiv to undo the injustice of July 1984, and to mend fences with him.

Rajiv Gandhi, at the very beginning, played hard to get, while he reiterated his support to G.M. Shah’s government. Personally, Rajiv was inclined to reinstalling Farooq; it seems that Rajiv’s advisers at the time, however, had persuaded him to position himself to ensure that when Farooq was reinstalled, it would he on New Delhi’s terms.

This turn of events put Farooq in a dilemma. He even considered lining up with the Opposition but realised that such a strategy would take him a while to come back to power, and he was unsure if he could sustain his supporters’ morale for too long.

Farooq was, nevertheless, forced to explore the other option. On 30 March 1985, he met N.T. Rama Rao in New Delhi, and both discussed floating a new party, “Bharat Desam”, which would be a national front of regional Opposition parties. Within Kashmir, he went about projecting himself as Riyasat ki Tehrik-e-Hurriyat ki Alamat (symbol of the state’s freedom movement). In April, he declared: “Our patience has been exhausted to the limit and if justice is not done, the bridge which links us with India will be broken.”

Farooq called for a Kashmir bandh in May, and it was a success. People had begun to get agitated under Shah’s oppressive regime. Prophetically, Farooq warned of a Punjab-like situation unless G.M. Shah was dismissed: “The present movement launched by us will pass into the hands of those over whom we have no control”, he threatened.

Finally, on 8 August 1985, Farooq and his mother met Rajiv Gandhi, and the meeting went off well enough to give Farooq the confidence that a settlement would be reached. His current allies warned him against it. Mirwaiz Farooq felt it would be a “betrayal of the people of the state” and would “erode people’s faith in the democratic set-up”.

Seeing the writing on the wall, G.M. Shah offered to step down from power when he returned from Haj on 4 September. Even Mufti Mohammad Sayeed threatened to

withdraw support, and in November, Shah made a last attempt to save himself by offering to mend fences with Farooq, provided a new Chief Minister was chosen from outside their families.

The proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back came soon after a judicial order directing the reopening of the disputed mosque in Ayodhya in January 1986. Riots broke out in the Valley, and several temples were torched in retaliation. February was a month of violence, curfew, flag marches and tension, and so, in March, the Congress withdrew support to G.M. Shah’s ministry. It fell and Governor’s rule was imposed.

Farooq now began to demand early polls, but an understanding between him and Rajiv Gandhi seemed elusive until 12 May 1986, when Mufti Mohammad Sayeed was taken out of the state and inducted into Rajiv Gandhi’s cabinet as Tourism Minister. After that Rajiv and Farooq met, and tried to thrash out the details of an understanding. Rajiv Gandhi wanted “no compromise with Farooq Abdullah at the cost of the Congress”, and Farooq retaliated by threatening to have all his MLAs resign from the house to force its dissolution.

In July, the Congress offered a coalition, and Farooq responded by saying he was not averse to it. The next month, the Government of India chose him to lead the goodwill Haj delegation to Saudi Arabia. When he returned, Transport Minister Rajesh Pilot discussed with him matters pertaining to the interim coalition government and electoral adjustments that could be made: they agreed that in the coming elections, the NC would contest 60 per cent of the seats, and the Congress, the remaining 40per cent. On 2 November 1986, the political understanding was announced to the world as the Rajiv-Farooq accord, and Farooq Abdullah was sworn in as Chief Minister on 6 November, with elections being announced for March 1987.

Farooq sought to rationalise the accord to his people by emphasising that it was vital for J&K’s economic development. It was a fact that the state economy was very fragile, and the problems on this front contributed in no small measure to the disaffection that led to numbers of youngsters entering the movement for azaadi a few years later.

For all the years since 1947, hand in hand with political deprivation, had come economic deprivation. As with several other states in the country (Bihar, or Assam, for instance), the Centre had practised a sort of “internal colonialism” with respect to Kashmir, keeping the Valley restricted to being a market economy. Indian goods and money came in, but the benefits were cornered by the unholy nexus comprising bureaucrats, politicians and capitalists. It was galling to most Kashmiris that their livelihood depended on the national highway. Everything, from vegetables to televisions, came via the road on the Banihal pass, which was subject to closure by avalanches during the winters, thus keeping the people at its mercy.

In addition, all the rich natural resources of the Valley, including timber, handicrafts and fruit, were lost as there was effectively no industrialisation in the state. Tourism was considered a ‘prostitute’ economy because it was felt that it brought no permanent gains to the Valley’s economy. Yet, even that had suffered: in 1989, J&K was behind Goa in tourist statistics even though it had been far ahead eight years earlier. Tourist arrivals had gone up only marginally, from 6.5 lakhs to 7.2 lakhs, due to lack of adequate facilities. The lacunae existed, even though tourism was the biggest revenue-generating activity after agriculture.

The Centre did not help out. Planning Commission figures show that, since 1975, there has been a decline in the state’s budgetary provisions. Not by accident, it was in 1975 that the party forming the government in Kashmir was different from the party in power at the Centre.

Keeping these realities in mind, Farooq and Rajiv sought to rationalise their understanding by saying that the alliance between the Congress and the NC would benefit the state as development projects with long gestation periods and massive capital investment requirements could be taken up for long-term economic gains. Two power projects, for instance, were envisaged: the 480 MW (megawatt), Rs. 4500 crore Uri project in the Valley, and the 380 MW Dulhasti project in Doda — one on the Jhelum river and the other on the Chenab.

It was a different matter that these two projects did not finally come through. In fact, nothing seemed to go right and the resultant continued unemployment of youth definitely became a factor in the militancy that erupted a few years later. For instance, till 1985, agricultural college graduates were being absorbed in jobs. Since then, however, there are about 500 who remain unemployed as are another 2000 engineering graduates. On 15 March 1988, many civil engineers who were unemployed made a show of burning their certificates in Srinagar. Even the JKLF in the 1990s would, at one stage, come to be known as the “engineers’ outfit”, following an influx of engineering graduates into the higher levels of its hierarchy.

In this background, Farooq had figured that if Delhi had a stake in the state government, it would be more responsive to J&K’s economic needs and would help push the state’s development rapidly forward. This was essentially the argument by which he hoped to sell the alliance to his people.

The Kashmiris, however, would not buy it. For them, it was the last straw. Not only did Farooq’s impatience to return to power seem undignified to Kashmiri Muslim pride, but he was also perceived to be “getting into bed” with the Kashmiri Muslim’s worst enemy — New Delhi. Arid once he was “sleeping” with the enemy, he was not going to be able to ensure the safeguarding of their political identity. No matter how loudly he shouted, and how often he claimed that he had not sold out — at Hazratbal, at Mujahid Manzil, at the medical college — no one wanted to listen to or believe him. The accord knocked the bottom out of his support.

All the other political elements in the Valley had seen what was coming, and had also grasped the growing discontent amongst the youth. Even ordinary bus accidents would lead to a crowd chanting slogans such as “Mard-e-Momin, Mard-e-haq, Zia-ul Haq” (a believer, a man of truth, the light of God).(Zia-ul-Haq was then the President of Pakistan.) Pakistan’s Independence day, 14 August, saw the illumination of the river banks of Baramulla, and the glow of candle light could be seen in the hostels of the University of Kashmir, overlooking Dal Lake. Groups such as Al Jehad and People’s League called for the observation of 15 August (India’s Independence Day) as a black day.

To make matters worse, Kashmiris felt that Muslims were generally being harassed all over India: they felt this was manifest in the Ayodhya issue, the Supreme court judgement on Shall Bano’s divorce settlement, the writ before the Kerala High Court for a ban on the Quran, and the rumours that Muslim policemen in Karnataka and Kerala were being forced to shave their beards.

So, on 21 April 1986, alternative political mainstream elements came together to form the United Muslims Front (UMF). This conglomerate of religious and political organisations was presided over by Shia leader, Moulvi Abbas Ansari. It included the Jamaat-e-Islami, the Jamaat-e-Tulaba, the Jamaat-e-Ahl-e-Hadis, the Anjuman TahafuzTul Islam’, the Muslim Employees Front, and the World Muslim Organisation. All of them were keen to politically cash in on the fact that Farooq had sold himself out to Rajiv Gandhi.

The worsening job situation fuelled the young Kashmir, Muslim’s discontent. Governor Jagmohan changed the criteria for job reservation so that the percentage of Muslim candidates selected by the Subordinate Services Recruitment. Board came down drastically. As Farooq would tell Syed Ali Shah Gilani in the Assembly a year later, the percentage of Muslims working in Central Government offices in J&K was only 5 per cent (33 out of 611 posts); in the banking sector only about 1.48 per cent (eight Muslims out of 448, employees); there were no Muslims in the Customs and Central Excise departments; only 18.87 per cent of the staff at the HMT watch factory were Muslims, while only 10.52 per cent were Muslims in the Accountant General’s office. In the state government, only 2795 employees were Muslims out of a total staff strength of 8370, a mere 33.39 per cent in a state where more than 60 per cent of the population was Muslim.

On 2 September 1986, the Mirwaiz of south Kashmir, Qazi Nissar Ahmed, defied Jagmohan’s order banning the sale of meat on Janmashtami (Hindu deity Lord Krishna’s birthday) by publicly slaughtering a sheep on a road in his native Anantnag. He was arrested, and the UMF was disbanded. In its place came into existence the Muslim United Front (MUF), launched “to protect and safeguard the basic right of the Muslim majority community in J&K”. Its spokesman, Professor Abdul Ghani, lambasted the “indiscriminate arrests of Muslim youth, the victimisation and harassment, discrimination in admissions to educational institutions and recruitment, and issuance of orders by the Jagmohan regime which were aimed at destroying the basic socio-political structure of J&K”.

Some of the charges against Qazi Nissar made amusing reading: he was accused of inciting people to withdraw money from national banks in order to weaken India, as also to produce more children, who could finally launch an armed rebellion against India. At his hearing at the Jammu High Court, however, Qazi Nissar told journalists that he was a “true nationalist fighting for rights within the framework of the Indian Constitution”. His dispute with Jamaat-e-Islami’s Gilani, over the finality of accession to India, would eventually threaten to split the MUF.

The MUF kept quiet over the accession issue, and announced its intentions to go to the polls. It received the support of the People’s League and the Islamic Students’ League. Mirwaiz Farooq stuck to his alliance with Farooq and was rewarded with two constituencies to contest from.

Election rallies got underway, and many a clash was seen between the supporters of the National Conference and the MUF. It was common to hear pro-Pakistan songs at MUF rallies, which swelled in size with each subsequent meeting. Interestingly, the MUF repeatedly called upon Kashmiri Muslims to liberate themselves from Delhi’s “Brahmin imperialism”. This was a direct call to the identity that had been at the core of Kashmir’s politics since 1931 and must have unnerved Farooq Abdullah.

The administration started acting high-handedly with the MUF. On 1 March 1987, three candidates were arrested: Srinagar Jamaat-e-Islami leader and Amirakadal candidate, Mohammad Yusuf Shah (who would later be known as Hizbul Mujahideen’s supreme commander Syed Salahuddin); Mushtaq Ahmed Sagar, of Habbakadal; and Syed Fayaz Naqshband of Hazratbal.

Despite the anxieties of the administration, observers predicted that multicornered contests would hurt the MUF in many places. Nonetheless, the taunts of Qazi Nissar worried the Chief Minister: Qazi Nissar declared that he would accept Farooq in the MUF if the latter repeated three slogans: “Assam ke katilon wapas jao” (killers of Assam, go back — a reference blaming the Congress for the massacre of Muslim refugees from Bangladesh in Nellie, Assam, in 1983); “Yeh mulk hamara hai iska faisla hum karenge” (we will decide the future of our land); and “Delhi walo khabardar hum Kashmiri hain tayyar” (beware, Delhi, we Kashmiris are prepared). There could be no clearer indication that the MUF felt that Farooq, having sold out to Delhi, had lost the right to represent the Kashmiri Muslims.

Ironically, Farooq had used the first slogan Qazi Nissar quoted during the 1983 elections. All he could do now was to threaten to jail the MUF leaders (for ten years in prisons outside J&K) if they continued to poison the minds of the people.

The news reports appearing during the week prior to the 23 March polling read like a police bulletin. Violent clashes took place every day, and on the day of the polling itself,

the turnout was 60 per cent but large-scale booth capturing and ballot box snatching were reported.

When the results eventually came in, the NC-Congress alliance swept the polls, winning around 60 seats, while the MUF, which won 31 per cent of the votes polled, bagged only five seats. The MUF alleged large-scale rigging and refused to accept the “officially manipulated verdict, which is nothing but a fraud [perpetrated] on the Constitution and democratic norms.”

Farooq now asserts that although he himself did no rigging, he “heard that some people indulged in rigging in some of the constituencies”. The MUF alleged that candidates such as Mohammad Yusuf Shah had been leading by a large margin throughout the counting, right until the final round, but then suddenly, they were declared losers. Sources close to Farooq at the time have since admitted that, for instance, in Amirakadal (the place from which Yusuf Shah contested), the election was rigged by the returning officer, who was later rewarded with the chairmanship of a local bank by the winning candidate, Ghulam Mohiuddin Shah.

Coming after a series of shocks in the 1980s — including Farooq’s dismissal, and his subsequent capitulation to New Delhi _ the allegations of rigging proved to be the proverbial last straw. Many MUF candidates and workers were picked up and thrown in jail including Mohammad Yusuf Shah and an election agent of his named Mohammad Yasin Malik. On the night of 26 March 1987 the police arrested over 60 MUF activists, raided their head office and seized their records. This action prompted rallies, sloganeering (‘ Rajiv-Farooq accord fraud fraud”), and threats of agitation (“We will do what Mrs. Aquino did in the Philippines”).

What was most telling was that there were no post-poll celebrations, as there had been in 1983 and in 1977. MUF activists started courting arrest. And according to one of the first militants ever to be caught by the state police, MUF activists sat in their jail cells and discussed going across to “Azad Kashmir”, where Pakistan had promised to provide them with arms and training, to help them in their fight against India.

An excerpt from Farooq Abdullah: Kashmir’s Prodigal Son – A Biography, Aditya Sinha, UBS Publishers Distributors. Read more about the book and buy it here.