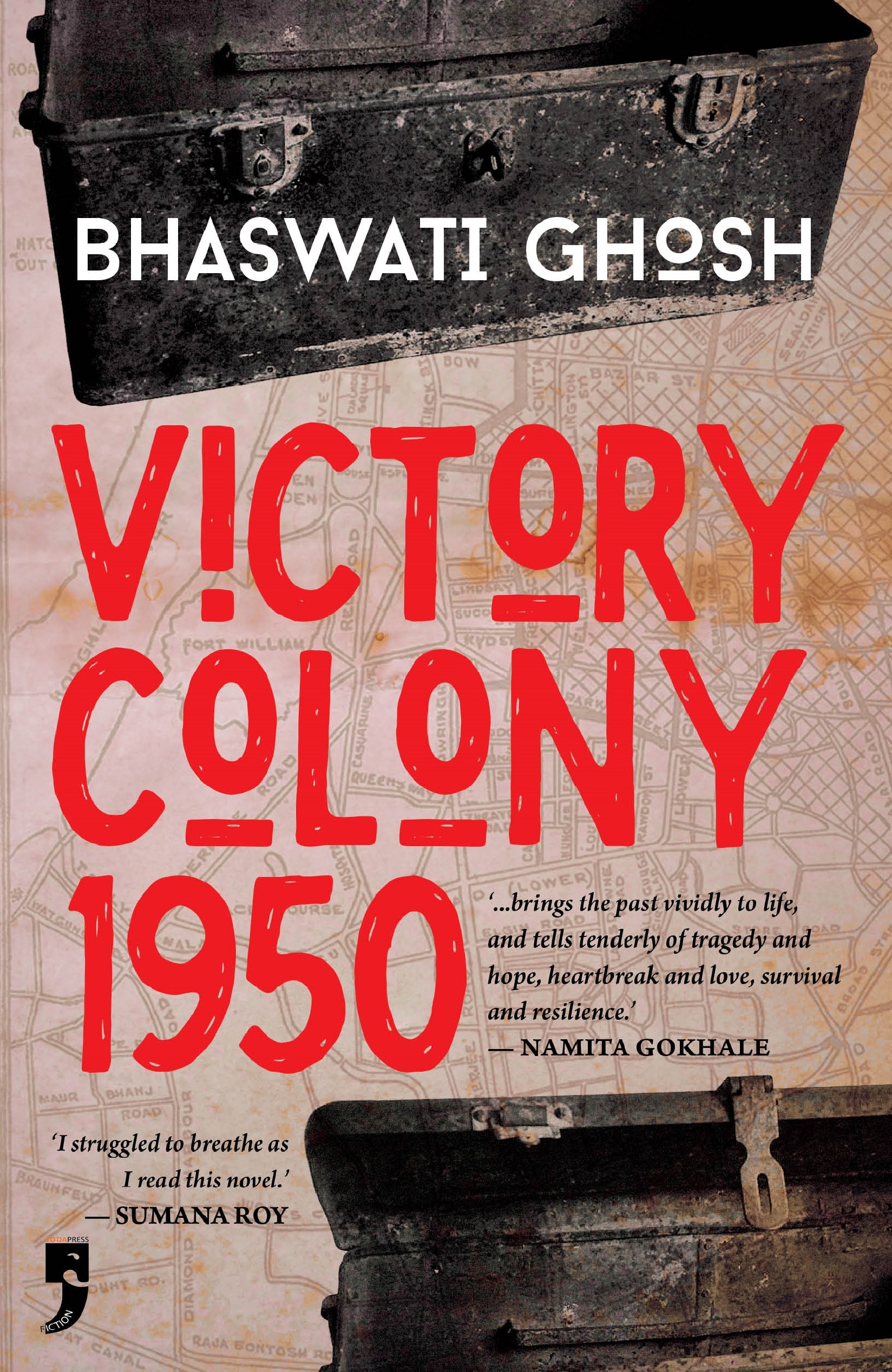

The book “Victory Colony, 1950” follows Amala Manna, who in 1949 has just crossed over to India from East Pakistan, and soon loses her younger brother Kartik. She makes her way to a refugee camp, but as official support dwindles and the camp situation deteriorates, the refugees take matters into their own hands, occupying a zamindar’s vacant plot of land and establishing Bijoy Nagar, meaning Victory Colony. The novel describes how the refugees built their lives from the bottom up with sheer hard work and persistence, changing, in the process, the socio-cultural landscape of Calcutta.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

Manas had little chance to interact with Amala over the past two days as the women were still holed up inside the school. The morning after the clashes ended, Manas and his friends took a tour of the freshly-seized squatter colony. Manas could see the enormousness of the task that lay ahead for the space to become truly habitable. There was no clean water supply or electricity. Nor did the residents have any sewage or waste collection system in place.

As they walked through the area, Subir thought aloud the need for setting up a few hand pumps at the very least. Manas nodded, saying they needed a new fundraising drive to get the basics in place in Bijoy Nagar.

‘We’ll also need more volunteers, Manas-da,’ Manik said.

Manas agreed as he thought of the added effort needed to manage the camp and work with the squatting refugees.

They landed close to Amala’s shack. The landlord’s goons had razed the incomplete fencing Amala had earlier put up. Manas saw Amala resurrecting the fence with a fresh batch of hogla leaves. She seemed engrossed in what she was doing. Manas noticed her lips moving with the hint of a sweet smile.

As the boys came closer, Manas said softly so as not to break Amala’s reverie, ‘Ei je, how goes?’

He thought he had caught a fragment of a song in her voice before it faded away as she looked at him and smiled. A tiny hurricane swept through Manas’s heart.

‘How are you all?’ Amala asked.

‘We are well, Didi,’ Manik said, ‘though we could do with some cha-muri.’

‘Why sure, Bhai,’ Amala said as she invited them in for tea.

Manas hesitated. ‘Nah, nah, please don’t bother. We have to visit the rest of your neighbours anyway.’

‘You surely have time for tea, Manas Babu,’ Amala said.

Her voice, courteous yet firm, surprised Manas. As did her calling his name for the first time ever. He quietly entered the tenement; Subir and Manik followed suit. Manas took in the scent of freshly-plastered mud on the walls. At the far end of the room, Malati swept with a broom. The moment she saw the boys, she covered her head with her anchal and beamed a smile, flashing her paan-reddened teeth.

Putting the broom in a corner, Malati said to the boys, ‘Esho, baba, esho. Come sit,’ pointing to the lone handwoven rug spread on the floor.

The volunteers took their seats on the ground. Manas couldn’t help but notice how spotless the small, unventilated room looked. A long-necked earthen pitcher rested on a stool in a corner. In

another corner, a few jerry cans stood on the floor like soldiers on alert.

Amala followed the men into the room and said to Malati, ‘Mashi, I will get some water for the tea. Please give them water to drink for now.’ She reached for the jerry cans and picked up a couple.

‘Where will you get the water from?’ Manas asked Amala.

‘From the pond we have here,’ she said, ‘ei jaabo aar ashbo. Be back in a minute.’

‘May I join you?’ Manas asked, even as he got up. He couldn’t miss this chance.

‘Nah, nah, please don’t bother. It’s not too far away. You talk with Mashi here; I’ll be right back,’ Amala said.

‘Let me see where the pond is,’ Manas said and offered to carry one of the jerry cans.

Amala, clearly embarrassed, handed it to him and said, ‘Ashun, let’s go.’

They followed the ridge path the refugees had roughly carved out after clearing the land of shrubs and weeds. Amala remained quiet except when she greeted a passing neighbour or other women walking to the pond to fetch water or with piles of unwashed laundry. Manas was glad he had worn covered shoes. Pebbles, twigs and shards of glass filled the earth beneath his feet. He lifted his dhuti, not because he didn’t want it to get dusty but because he couldn’t afford to trip on this uneven terrain.

Manas broke the silence gathering between Amala and him. ‘So, how have you been?’

‘How do you find me to be?’ Amala said, her gaze still averted.

‘You seem to be doing fine,’ Manas said, adding with a chuckle, ‘now that you don’t have to listen to my odd requests.’

Amala laughed lightly. A few quiet moments followed.

‘So…so you ran away without saying goodbye to…’ Manas clipped back the last word, a pronoun for self. Amala heard it anyway.

‘You took so long to get well, Manas Babu,’ Amala said with a sigh. ‘How could I not join our people here, you tell me.’

‘Hey, I was only teasing you. Of course, you did the right thing. I am happy for you. In fact, I am…I’m proud of you.’

Amala remained quiet. They were just a few steps from the pond when she said, ‘Are you feeling better now?’

‘I am as well as you see me. And how is that?’

‘You look weak and thin. I hope you’re eating well.’

‘Oh yes, don’t worry about me,’ Manas said even as their conversation came to an abrupt end when they reached the pond.

Groups of women had scattered across the bank. Boys and girls of all ages were plunging into the pond’s cool, algae-green water for an afternoon dip. From the trees on the banks, crows and mynas created an odd sort of symphony as the birdcall blended with the women’s and kids’ giggles. Manas looked around and saw three or four men on the other side of the pond. They had a couple of fishing rods in the water, evidently in search of fresh catch for lunch. A mini village scene had taken shape, and it soothed Manas’s nerves.

‘It is good, Babu, our coming here,’ Amala’s words cut through Manas’s reverie.

‘Hmm, I see that,’ Manas said. ‘Better than that sickly camp for sure.’

‘Better than living on handouts,’ said Amala as she dipped a jerry can into the pond. Manas followed suit, if a bit reluctantly when he saw how mucky the water was. With the help of what Manas considered the sixth sense women were born with, Amala seemed to have read his mind.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said with a smile, ‘I will boil the water and strain it well for your tea. You won’t fall sick again, not because of me.’ Manas managed a faint smile, not enough to hide his embarrassment.

Excerpted with permission from Victory Colony, 1950, Bhaswati Ghosh, Yoda Press. Read more about the book here and buy it here.