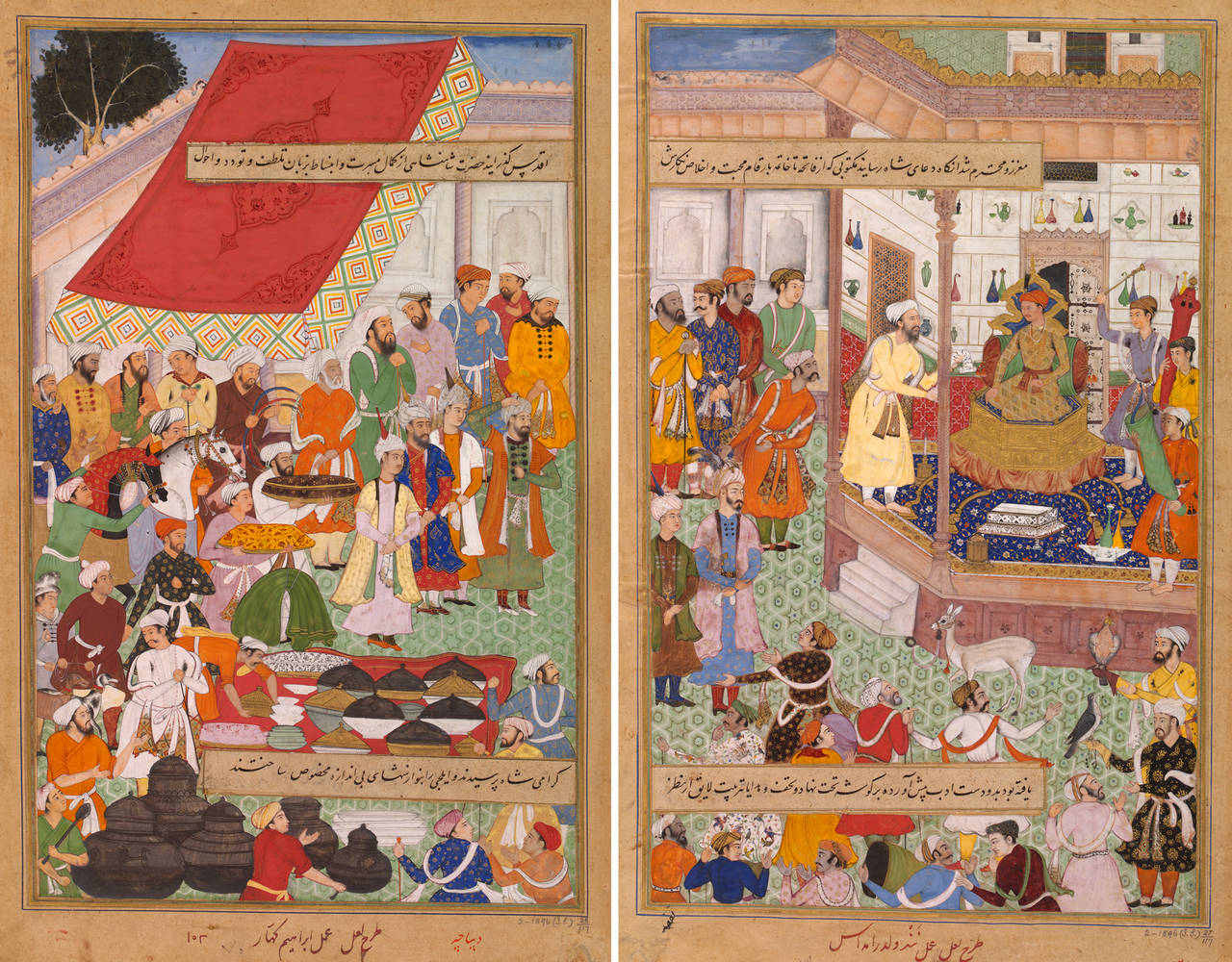

The book “Reflections on Mughal Art and Culture”, edited by Roda Ahluwalia, explores the rich aesthetic and cultural legacy of Mughal India through fresh insights offered by 13 eminent scholars.

Diversity of themes, such as portraits of royal women, the lapidary arts and the Imperial Library of the Mughals have been discussed and analyzed in this anthology.

Over 175 images of Mughal artifacts, paintings, gardens and monuments illustrate the lasting heritage of the Imperial Mughals, and this beautifully illustrated book is sure to appeal to connoisseurs, collectors and scholars alike.

Read an excerpt from the book “Reflections on Mughal Art and Culture” below.

Editor’s Note: The following excerpt has been taken from the chapter “The Lapidary Arts in the Mughal Empire”, in which Susan Stronge writes on the Lapidary Arts in the Mughal Empire, referring to a range of objects made of hardstone materials such as aventurine quartz, agate, rock crystal and nephrite jade, and highlighting objects in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

****

From the late 16th century, and almost certainly before this, master craftsmen within the imperial Mughal workshops worked on a range of hardstone materials. This is apparent from the A’in-e Akbari, the survey of the institutions of Akbar’s reign completed for the emperor by the learned historian Abu’l Fazl in 1596.

In a section of his text entitled ‘The Workers in Encrusted Wares’, Abu’l Fazl notes that the specialist zarnishan, or gold inlayer, is a craftsman who also ‘cuts agate, crystal and other gems in various ways and sets them in gold … He embellishes agates and other stones by engraving and cutting them’. One of these is later mentioned by name: Mawlana Ibrahim of Yazd was one of the renowned masters of the age in engraving calligraphy on agate.

The very long tradition in the subcontinent of shaping agate into beads and vessels is well known and predates the arrival of the Mughals by centuries. Gujarat was, and still is, the major centre of production for agate and its heat-treated version, carnelian, with its characteristic deep orange hues. Objects made in Khambat (Cambay) supplied foreign markets from early times, travelling as far as the Roman Empire.

Rock crystal occurs in many locations across the subcontinent. It too was used to make beads and small objects, as attested by frequent literary references and the existence of actual artefacts, including seals, ritual objects from Buddhist stupas, and miniature statuettes made for portable Jain shrines. Items made during the Mughal period, but not within the empire, reached European collections as early as the late 16th century. A rock crystal bangle set with rubies and sapphires in gold appears in an English inventory of 1587. It was supposedly sent by Akbar to Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) but the setting of its stones compares closely with similar settings on rock crystal statuettes of Christ and other artefacts made in Goa or Sri Lanka under Portuguese influence.

****

- Feature Image. Akbar receives the Iranian Ambassador Sayyid Beg in 1562, illustration to the Akbarnama, by Farrukh Beg. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Figure 1. Wine bowl, green aventurine quartz. Mughal, seventh regnal year of Shah Jahan (1612–13). Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, Rhode Island

- Figure 2. Wine bowl (detail of the underside), green aventurine quartz. Mughal, 1612–13. Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, Rhode Island

****

Considerable ability is required to make artefacts of agate, carnelian or rock crystal, and to embellish their surfaces with fine calligraphy. These hardstones cannot be carved, and objects must be shaped by using a bow drill to manipulate lap wheels of different sizes and diamond points, wearing away the surface of the stone with an abrasive powder suspended in water.

The same tools and techniques are used to shape nephrite jade, which is not found in the subcontinent. From the late 16th century, it may have been available to the Mughals in unworked blocks brought from its sources in Khotan. No finished artefacts of Akbar’s reign have been conclusively identified, but nephrite jade was used to make vessels for the emperors Jahangir (r.1605–1627) and Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658), as their dated inscriptions demonstrate. Art history has focused heavily on these and other undated jade objects of the same period. Surprisingly little attention has been paid to the simultaneous use of agate, rock crystal and other hardstones in the royal ateliers.

A rare dated green aventurine quartz wine bowl was made for Jahangir, as the Persian verses engraved round the rim in very fine nasta’liq proclaim (Fig. 1). On the underside, another inscription states that the bowl was made in the seventh year of his reign, indicating that it was completed between March 1612 and March 1613, almost certainly to be presented at Nowruz (Fig. 2). The calligraphy has been identified as the hand of Sa’ida-ye Gilani by A.S. Melikian-Chirvani in his important study of the Iranian master lapidary who was also the head of the goldsmiths’ department under Jahangir and Shah Jahan. The quatrains include a hemistich that is repeated on another wine cup made for Jahangir, dated to the following year and also attributable to Sa’ida.

Inexplicably, the main decoration in a broad band on the outer surface of the Rhode Island bowl, beneath the calligraphic border round the rim, is unfinished. Eight flowering plants contained within lobed and cusped cartouches are undercut to leave them reserved in low relief against the smooth walls of the bowl, but their details are only lightly incised, the contours are somewhat roughly formed, and the undercut surface of the quartz has not been polished.

Excerpted with permission from the essay “The Lapidary Arts in the Mughal Empire” by Susan Stronge, from Reflections on Mughal Art and Culture, edited by Roda Ahluwalia, Niyogi Books. Read more about the book here and buy it here.

Excerpted with permission from the essay “The Lapidary Arts in the Mughal Empire” by Susan Stronge, from Reflections on Mughal Art and Culture, edited by Roda Ahluwalia, Niyogi Books. Read more about the book here and buy it here.