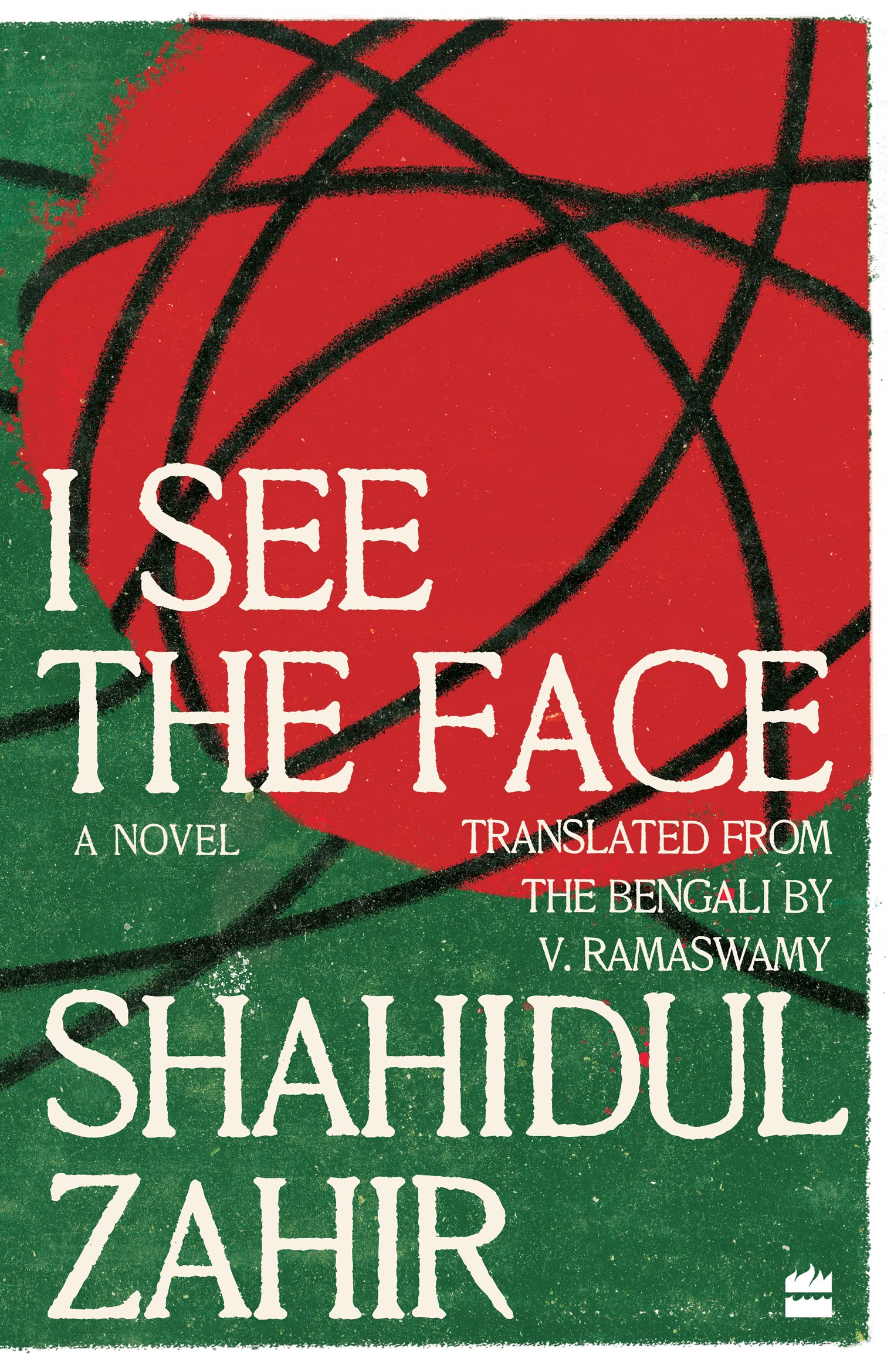

The book “I See The Face” by Shahidul Zahir has been translated from the Bengali by V. Ramaswamy.

Moving effortlessly from the past to the present, and back again, Zahir paints a picture of the crisis of post-independence Bangladesh and describes how society or the State drives a poor but brilliant boy to destruction.

There is biting wit and humour, and above all, a kind of ethereal understatement which make the reading experience an incomparable one.

Read an excerpt from the book below.

Perhaps Chan Miya of Ghost Lane had been nourished by monkey’s milk as an infant, because if you ever met someone like, say, Mamun and Mahmud’s Ma, Mrs Zobeida Rahman, who was witness to that, at her residence in No. 25, and if the conversation turned to the subject of Chan Miya, she never forgot to say, ‘O toh bandorer dudh khaichhilo. But he was raised on monkey’s milk,’ and if anyone ever cast doubt on that, she would definitely get into an argument and, if necessary, quarrel. For instance, take Fakhrul Alam Ledu, he was Mamun’s childhood friend, they were both first-year Intermediate students; let’s say he went to Mamun’s house one day to meet him, but maybe Mamun was not at home then, something like that could definitely have happened, Ledu might have gone there, and Mamun may well not have been at home then, and so it would be a most normal thing for Mamun’s Ma to meet Fakhrul Alam Ledu when she emerged from her room. And after that, if Mamun’s Ma said, ‘Since you’re here, come, have a cup of tea,’ and if Fakhrul Alam Ledu agreed, then in that case, the situation would have been created for some stray conversation between Ledu and Mamun’s Ma as they sat together in the house; the subject of Chan Miya could have come up in the course of this conversation, and if Fakhrul Alam Ledu expressed any doubts in that connection, Mamun and Mahmud’s Ma would definitely have told him, ‘You know nothing!’

But why wasn’t Mamun ul Hye, aka Mamun, at home? And so Fakhrul Alam Ledu asked Mamun’s Ma, ‘Where’s Mamun, where’s he gone?’ Perhaps Mamun’s Ma knew where he had gone, or maybe she didn’t know, perhaps she said, ‘I don’t know where he’s gone,’ or perhaps she said, ‘He went to fetch sawdust.’ Mrs Zobeida Rahman used a sawdust-fired stove in her kitchen.

Perhaps one day, because Mamun’s school was closed, he left home with an empty wheat sack – the same one which his Ma had lengthened by stitching another sack on to it – and proceeded towards the timber yard in Nayabazar. Perhaps he walked down Twin Bridge and Lalchan Mokim Lane and then made his way through Malitola, and presented himself at The New Chondroghona Saw Mill & Timber Depot, perhaps it was raining that day and the sawmill had closed in the evening after running all day, and after reaching there and bargaining with some employee or sawyer about the price of sawdust, when a price of three taka for a sack was finally agreed upon, he descended into the pit of sawdust at the base of the siris tree in the sawmill. The dust from the wood sawn all day had accumulated in the pit, so upon descending into this pit and seeing the mountain of sawdust there, perhaps a kind of elation came over Mamun, like it did over Ali Baba of yore, and perhaps on account of being rapt, or perhaps for some other reason, he somehow got buried under a mound of sawdust while trying to fill his sack, and since the employees of the mill didn’t notice it, he remained concealed like that. That night, four five-ton trucks belonging to Abdul Wodood Chowdhury, the brother of the sawmill owner, Abdul Mabud Chowdhury, were parked in front of The New Chondroghona Saw Mill& Timber Depot, and a group of coolies, or porters, who were ready in advance carried baskets of sawdust from the pit and emptied them over some white sacks that were already inside, thus concealing them. The coolies asked the drivers of the trucks, ‘What’s going today?’ But the drivers of the trucks didn’t reply, they frowned and looked deadpan as they sat with a lordly air, their hands on the steering wheels, but nothing was lost thereby, because these coolies were extremely intelligent, they reckoned, ‘It’s fertilizer, going to Burma.’ Or perhaps these coolies weren’t intelligent, but be that as it may, the problem that should have arisen in this regard, irrespective of whether the coolies were intelligent or otherwise, did arise, and Mamun Miya left Dhaka for Chittagong along with the fertilizer and sawdust. This is how it happened: while these intelligent, or stupid, coolies were loading their baskets with sawdust, they certainly found him; perhaps he was lying unconscious within a mound of sawdust when they discovered him, but given that they were unable to turn the lights on while working, and therefore it was dark inside the mill, they bundled the curled-up, unconscious Mamun into a basket and threw him into one of the trucks, but it did occur to them that perhaps it was a piece of wood, it wasn’t far-fetched on their part to think so, after all they were coolies who were the offspring of coolies, and so they thought that whatever lay within sawdust couldn’t be anything other than wood, perhaps it was something expensive, like teak or beech, it could also be siris or gorjon, or some sundry tree, like kadam or chhatim, or perhaps just any kind of wood. Or perhaps they didn’t think along those lines, perhaps they were not so stupid, and when they were using their hands to load the sawdust into their baskets and found Mamun ul Hye lying there, they realized, notwithstanding the darkness, that it was a human and not a block of wood, because they found that it had two arms, two legs and a head, and these coolies knew that it was humans who had two arms and two legs and a head, and so they got scared, it occurred to them that perhaps this was a corpse, and then they displayed their intelligence: without saying a word, they carried Mamun in a basket and dumped him into one of the trucks, because they thought that if they tried to report this matter now it was they who would get in trouble with the police, who would ask them a thousand and one questions, perhaps they’d kick and punch them too, so it was best to dispatch the object found in the mill owner’s sawdust in the lorry belonging to his brother!

Perhaps Mamun was unconscious as he lay in the sawdust, and so when the lorry left for Chittagong late at night, he wasn’t aware of anything; and because it had been raining that day, the trucks had tarpaulin covers, and whenever these trucks departed from Nayabazar, they went down the road beside Dholaikhal, turned at the Jatrabari crossroads and got on the road to Chittagong. It’s difficult to say where exactly the trucks would have gone to unload the goods that day, the stuff might have been loaded on a trawler or a sampan in Chittagong at either the Firingibajar or Sadarghat docks, or at the foot of the Kalurghat bridge, but before that the trucks fell into the clutches of the police mobile squad near Chouddogram, in Cumilla District, and although the police were able to halt three trucks, one truck didn’t stop, and amidst the fluster, the veteran driver quickly turned into some side road and escaped. But perhaps the truck driver got scared, and so he took the truck directly to Satkania where the export merchant Abdul Wodood’s village house was, or perhaps the truck went to Firingibajar or Sadarghat, and when the merchant’s employees there heard about the trucks having been chased by the police, they decided that the goods ought to be taken to the village house. So in this way, Mamun Miya arrived, together with the consignment of urea to be smuggled, at Abdul Wodood Chowdhury’s house in Boyaliyapara, in the Satkania locality of Chittagong District, and after that he encountered Asmantara Hoore Jannat; and so one day Mamunul Hye’s Ma narrated to Fakhrul Alam Ledu the story of Chan Miya, and told him, ‘Just go and ask Chan Miya’s Ma, Khoimon, who suckled him.’ Perhaps that was because there were monkeys in the moholla during Chan Miya’s infancy, and those monkeys could be seen on the roofs and walls of the houses in the moholla, with their brown backs, whitish bellies and red backsides; they used to walk along walls or lie on the parapet of some house with their tails dangling. Perhaps there were one, or two, or many, female monkeys in this troop of monkeys then, with the baby monkeys clinging to the breasts of the female monkeys and swaying between their legs. Perhaps Chan Miya had drunk the milk of some she-monkey like that when he was an infant, when his Ma, Mochhammot Khoimon Begum, aka Khoimon, left him unattended at home, latching the door from outside, and proceeded from her house on No. 36 to the house of Nurani Bilkis, aka Upoma Begum, at No. 37, and requested her, ‘Aafa, amare ek kaap chini dhar daen. Aapa, please lend me a cup of sugar.’

Excerpted with permission from I See The Face: A Novel, Shahidul Zahir, translated from the Bengali by V. Ramaswamy, HarperCollins India. Read more about the book here and buy it here.