The book “A New Silk Road: India, China and the Geopolitics of Asia” by Kinshuk Nag offers deep, unknown insights into the political, economic, social and cultural factors underlying the current state of Sino-Indo relations.

The book details China’s new ‘great game’ in the Himalayas — to continue to take over large parts of Ladakh to suit the interests of the CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), that is a key element in its Belt and Road Initiative, along with simultaneously continuing trade ties.

The author re-examines outdated assumptions and makes path-breaking discoveries about China’s ambitions, and insists that India and China are vastly different nations with very diverse political and economic strategies—something that Indians must understand in order to counter the Chinese conundrum.

Read an excerpt from the book “A New Silk Road” below.

In present-day China, the mention of the Silk Road evokes memories of the greatness of the nation more than a thousand years ago and the resultant prosperity. Thus, when the post-Deng Xiaoping rulers of China (around the year 2000) realized that the country had developed sufficiently and sat on a pile of foreign exchange, they averred that they could recreate a modern-day Silk Road. This would allow China to dominate the world once again, as their surplus money would be used for investment in countries that were on the new Silk Road to create highways, rail lines and other infrastructure like power grids, maritime ports, and oil and gas pipelines. The countries where the money is invested would get it at perceptibly low interest rates and easy repayment terms, and China would also benefit because, along with the investment, jobs would be created. The Chinese government planned it such that the works would be handed over to companies in China and the countries were even encouraged to bring in labour from China. All this would boost China’s economy. Countries where funds from China are deployed would generally become dependent on the latter and become obliged to China as well. This, thus, acts as a means of foreign policy, where these countries could be diplomatically influenced by China.

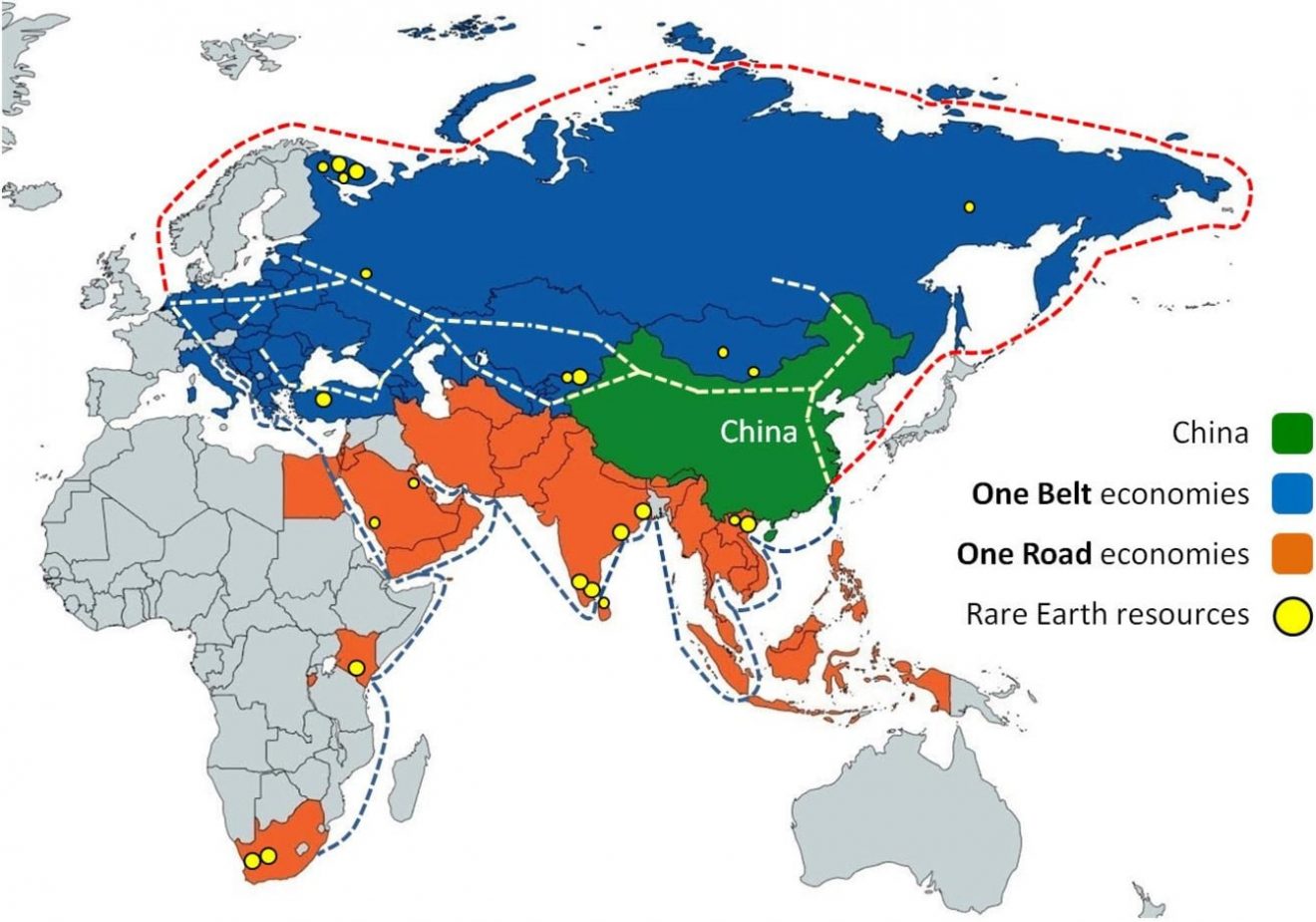

In 2013, China unveiled a grand plan—the One Belt One Road policy, or OBOR—credited to President Xi Jinping. It is also known as the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI. It is mainly on the old Silk Road route but has been extended to new territories. The OBOR, in fact, was built on the ‘Going Out’ policy started by Deng Xiaoping in the 1990s and given fillip by the next president (1993–2003), Jiang Zemin, to globalize the Chinese economy and its currency.

The project covers two parts. The first is called the Silk Road Economic Belt, which is primarily land-based and will connect China with Central Asia, and Eastern and Western Europe. The second part of the project is called the Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Road. It is seabased and connects South China to the Mediterranean, Africa, Southeast Asia and Central Asia. In fact, as conceived by the Chinese, the project is targeted to have six components:

- the New Eurasian Land Bridge, connecting western China to western Russia;

- the China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor, connecting north China to eastern Russia via Mongolia;

- the China–Central Asia–West Asia Economic Corridor, connecting western China to Turkey via Central and West Asia;

- the China–Indochina Peninsula economic corridor, connecting southern China to Singapore via IndoChina;

- the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, connecting southwestern China to the Arabia Sea routes via Pakistan; and

- the Bangladesh–China–Myanmar corridor, connecting southern China to Myanmar and Bangladesh.

India was proposed to be part of the last mentioned corridor, but there is strong opposition from the Indian government to be part of this initiative.

The OBOR plan does not only use the foreign exchange in other countries but is also designed to increase growth in parts of China that are not developed. This includes Xinjiang in northwestern China, which is woefully lacking in development. Other states chosen are inner Mongolia in northeast China, Guangxi in southwest China and Fujian on the southeastern coast.

China perceives that OBOR will ultimately cover 70 countries and will be completed by 2049 (which will incidentally mark a hundred years of the PRC). If OBOR is implemented in the way China wants, it will catapult the nation to a position of great power.

China knows that a huge amount of funds will be required to make the massive programme successful. In 2017, China pledged an amount of $113 billion for OBOR to be disbursed through the state-owned Silk Road Fund (established in 2015). Another $40 billion of initial capital will be provided by the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China. In addition, the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) will provide $100 billion and the Shanghai-based New Development Bank will make available $50 billion.

Though many countries that will benefit from the OBOR are quite optimistic and buoyant, many others are seeing the danger. There are apprehensions that China would start meddling in the functioning of their economies and governments, which will benefit from the large fund infusions from the OBOR. Aware of these, China is now claiming that ‘there will be no interference in the internal affairs of countries’ and that it will not seek to ‘increase its sphere of influence’ or strive for ‘hegemony or dominance.’ But smaller countries with weak political systems, even if they are able to figure out the possibility of Chinese dominance, choose to look the other way because of all the money they will get. As an example, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are excited about the OBOR because China will make massive investments in local transmission projects. Landlocked Nepal is also very positive as it will facilitate cross-border connectivity with China (across the mountains). Usually it’s the smaller countries that are looking forward to the investments, which they view as a windfall gain. India, as mentioned before, has serious issues about the OBOR and has refused to join in (although China has made serious efforts to persuade India). A deeper understanding of the reasons is therefore mandatory.

Excerpted with permission from A New Silk Road: India, China and the Geopolitics of Asia, Kinshuk Nag, Rupa Publications. Read more about the book here and buy it here.